Hardware Solutions To Highly-Adversarial Environments Part 1: Whitebox Crypto vs Smart Cards vs Secure Elements vs Host-Card Emulation (HCE) posted March 2020

If at some point you realize that doing cryptography means having to manage long-term keys, it means you’re standing in the world of key management.

Makes sense right?

In these lands, you are going to run into scenarios where attackers can be quite close to your applications. I call these highly-adversarial environments.

Imagine using your credit card on an ATM skimmer (a doodads that a thief can place on top of the card reader of an ATM in order to copy the content of your credit card, see picture bellow); downloading an application on your mobile phone that compromises the OS; hosting a web application in a colocated server shared with a malicious customer; managing highly-sensitive secrets in a data center that gets breached; and so on.

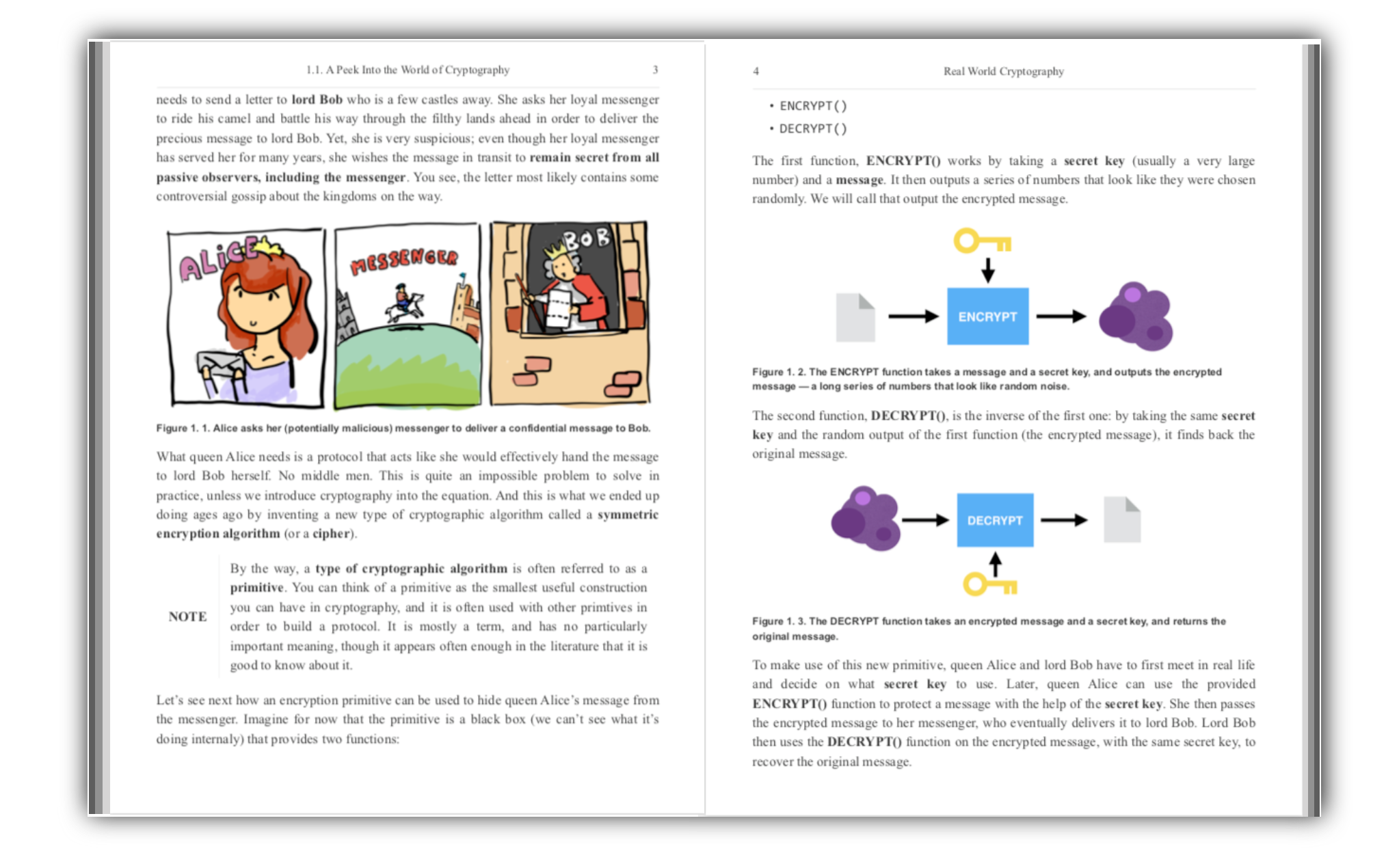

These scenarios suck, and are very counterintuitive to most cryptographers. This is because cryptography has come a long way since the historical “Alice wants to encrypt a message to Bob without Eve intercepting it”. Nowadays, it’s often more like “Alice wants to encrypt a message to Bob, but Alice is also Eve”.

The key here is that in these scenarios, there’s not much that can be done cryptographically (unless you believe in whitebox crypto) and hardware can go a long way to help.

OK, so now we have a whole world of new doohickeys to learn about, and there’s a lot of thingamabob believe me (hence the dense title). It can be quite confusing to learn about all of this, so here we go: my promise is that by the end of this blogpost series you’ll have a better understanding of what are all these different hardware solutions.

Keep in mind that none of these solutions are pure cryptographic solutions: they are all defense-in-depth (and sometimes dubious) solutions that serve to hide secrets and their associated sensitive cryptographic operations. They also all have a given cost, meaning that if a sophisticated attacker decides to break the bank, there’s not much we can do (besides raising the cost of an attack).

OK let's get started.

Obfuscation

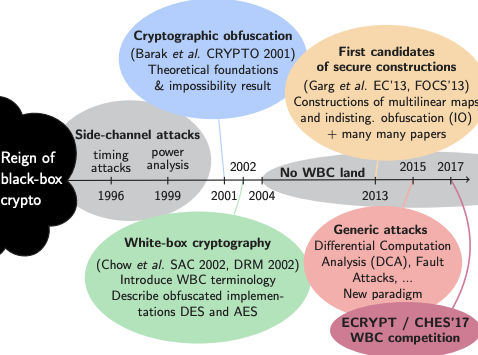

By definition obfuscation has nothing to do with security: it is the act of scrambling something so that it still work but is hard to understand. So for the laugh, let’s first mention whitebox cryptography which attempts to “cryptographically” obfuscate the key inside of an algorithm. That’s right, you have the source code of some AES-based encryption algorithm with a fixed key, and it encrypts and decrypts fine, but the key is mixed so well with the implementation that it is too confusing for anyone to extract the key from the algorithm. That's the theory. Unfortunately in practice, no published whitebox crypto algorithm has been found to be secure, and most commercial solutions are closed-source due to this fact (security through obscurity kinda works in the real world). Again, it’s all about raising the cost and making it harder for attackers.

All in all, whitebox crypto is a big industry that sells dubious products to businesses in need of DRM solutions. On the more serious side, there is a branch of cryptography called Indistinguishability obfuscation (iO) that attempts to do this cryptographically (so for realz). iO is a very theoretical, impractical, and so far not-really-proven field of research. We’ll see how that one goes.

(Timeline of whitebox cryptography, taken from Matthieu Rivain’s slides)

Smart Cards

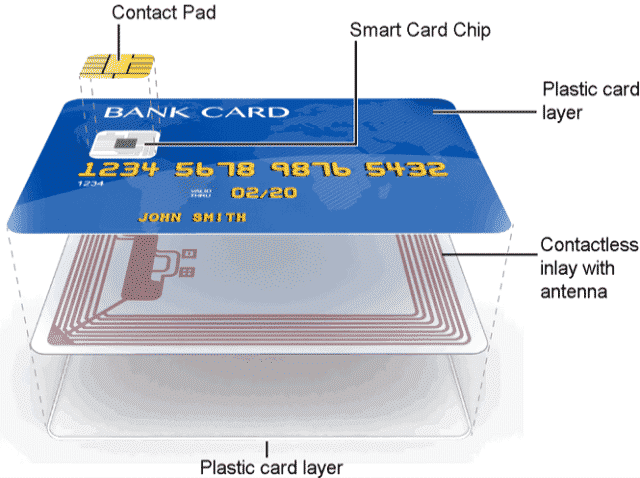

OK, whitebox crypto is not great, and worse: even if you can’t extract the key, you can still copy the program instead of trying to extract the key (and use it to do whatever cryptographic operation it features). It would be great if we could prevent people from copying secrets from sensitive devices though, or even prevent them from seeing what’s going on when the device performs cryptographic operations. A smart card is exactly this. It’s what you commonly find in credit cards, and is activated by either inserting it into, or using Near-field Communication (NFC) by getting the smart card close enough to, a payment terminal (also called Point of Sale or PoS terminal).

Smart cards are pretty old, and started as a practical way to get everyone a pocket computer. Indeed, a smart cart embarks a CPU, memory (RAM, ROM and EEPROM), input/output, hardware random number generator (so called TRNGs), etc.) unlike the not-so-smart cards that only had data stored in them via a magnetic stripe (which in turn can be easily copied via the skimmers I talked about previously). Today, it seems like the same people all have a much more powerful computer in their pockets, so smart cards are probably going to die. (Rob Wood is pointing to me that more than a quarter of the US still doesn’t have a smart phone, so there’s still some time before this prophecy come to fruition.)

Smart cards mix a number of physical and logical techniques to prevent observation, extraction, and modification of its execution environment and some of its memory (where secrets are stored). But as I said earlier, it’s all about how much money you want an attacker to be spending, and there exist many techniques that attempt at breaking these cards:

- Non-invasive attacks such as differential power analysis (DPA) analyze the power consumption of the smart card while it is doing cryptographic operations in order to extract the associated keys.

- Semi-invasive attacks require access to the chip’s surface to mount attacks such as differential fault analysis (DFA) which use heat, lasers, and other techniques to modify the execution of a program running on the smart card in order to leak the key via cryptographic attacks (see my post on RSA signature fault attacks for an example).

- Finally invasive silicon attacks can modify the circuitry in the silicon itself to alter its function and reveal secrets.

Secure Elements

Smart cards got really popular really fast, and it became obvious that having such a secure blackbox in other devices could be useful. The concept of a secure element was born: a tamper-resistant microcontroller that can be found in a pluggable form factor like UUICs (SIM cards required by carriers to access their 3G/4G/5G network) or directly bonded on chips and motherboards like the embedded SE (eSE) attached to an iPhone’s NFC chip. Really just a small separate piece of hardware meant to protect your secrets and their usage in cryptographic operations.

SEs are an evolution of the traditional chip that resides in smart cards, which have been adapted to suit the needs of an increasingly digitalized world, such as smartphones, tablets, set top boxes, wearables, connected cars, and other internet of things (IoT) devices. (GlobalPlatform)

Secure elements are a key concept to protect cryptographic operations in the Internet of Things (IoTs), a colloquial (and overloaded) term to refer to devices that can communicate with other devices (think smart cards in credit cards, SIM cards in phones, biometric data in passports, garage keys, smart home sensors, and so on).

Thus, you can see all of the solutions that will follow in this blogpost series as secure elements implemented in different form factors, using different techniques, and providing different level of defense-in-depth.

If you are required to use a secure element (to store credit card data for example), you also most likely have to get it certified. The main definition and standards around a secure element come from GlobalPlatform, but there exist more standards like Common Criteria (CC), NIST’s FIPS, EMV (for Europay, Mastercard, and Visa), and so on. If you’re in the market of buying secure microcontrollers, you will often see claims like “FIPS 140-2 certified” and “certified CC EAL 5+” next to it. Claims that can be obtained after spending some quality time, and a lot of money, with licensed certification labs.

Host Card Emulation (HCE)

It’s 2020, most people have a computer in their pocket: a smart phone. What’s the point of a credit card anymore? Well, not much, nowadays more and more payment terminals support contactless payment via the Near-field Communication (NFC) protocol, and more and more smartphones ship with an NFC chip that can potentially act as a credit card.

NFC for payment is specified as Card Emulation. Literally: it emulates a bank card. Banks allow you to do this only if you have a secure element.

Since Apple has full control over its hardware, it can easily add a secure element to its new iPhones to support payment, and this is what Apple did (with an embedded SE bonded to the NFC chip since the iPhone 6). iPhone users can register a bank card with the Apple wallet application, Apple can then obtain the card’s secrets from the issuing bank, and the card secrets can finally be stored in the eSE. The secure element communicates directly with the NFC chip and then to NFC readers, thus a compromise of the phone OS does not impact the secure element.

Google, on the other hand, had quite a hard time introducing payment to Android-based mobile phones due to phone vendors all doing different things. The saving technology for Google ended up being a cloud-based secure element called Host Card Emulation (HCE) introduced in 2013 in Android 4.4.

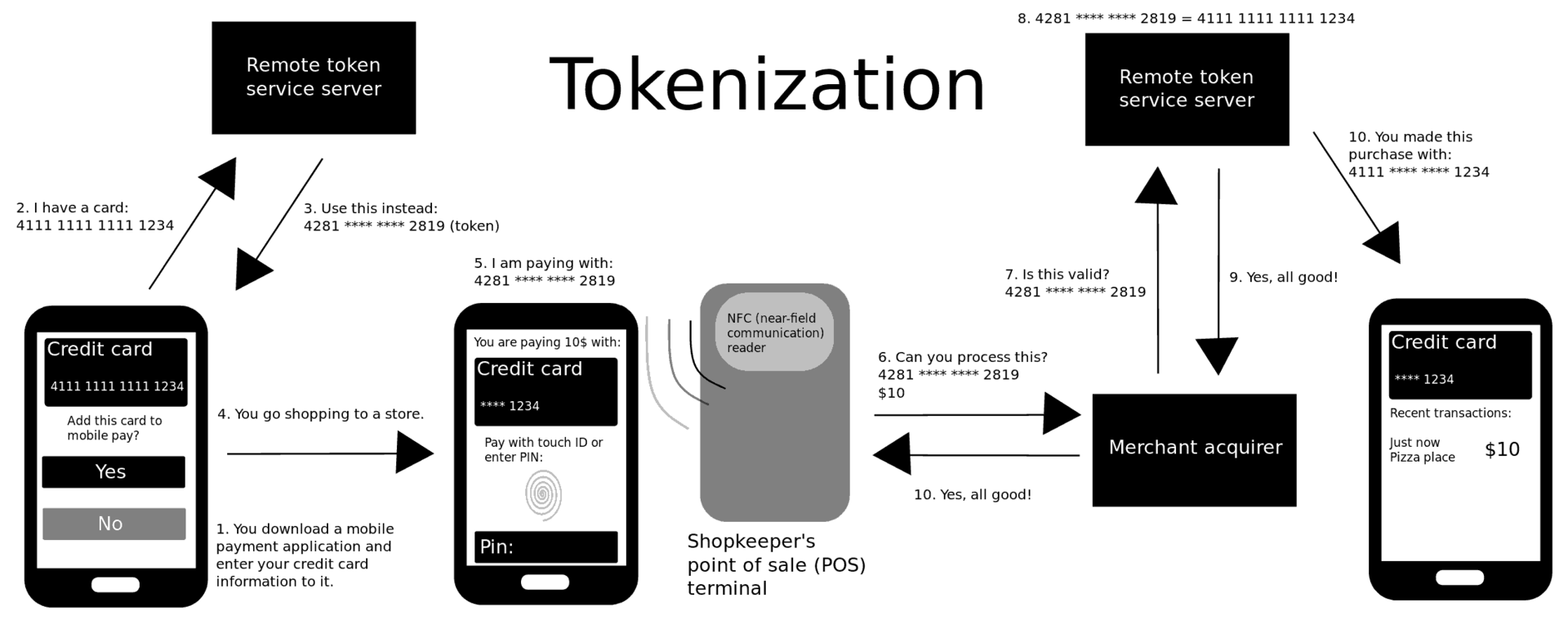

How does it work? Google stores your credit card information in a secure element in the cloud (instead of your phone), and only gives your phone access to short-lived single-use PAN (card numbers). (Note that some Android devices do have an eSE that can be used instead of HCE, and some SIM cards can also be used as secure elements for payment.) This concept of replacing sensitive long-term information with short-lived tokens is called tokenization. Sending a random card number that can be linked to your real one is great for privacy: merchants can’t track you as it’ll look like you’re always using a new card number. If your phone gets compromised, the attacker only gets access to a short-lived secret that can only be used for a single payment. Tokenization is a common concept in security: replace the sensitive data with some random stuff, and have a table secured somewhere safe that maps the random stuff to the real data.

Wikipedia has some cool diagram to show what’s going on whenever you pay with Android Pay or Apple Pay:

Although Apple theoretically doesn't have to use tokenization, since iPhones have secure elements that can store the real PAN, they do use it in order to gain more privacy (it's afterall their new bread and butter).

In part 2 of this blog series I’ll cover HSMs, TPMs, and much more :)

(I would like to thank Rob Wood, Thomas Duboucher, and Lionel Rivière for answering my many questions!)

PS: I'm writing a book which will contain this and much more, check it out!

Comments

david

I guess one detail that could be important in defining a smart card and more generally a secure element: they run javacard.

> Java Card refers to a software technology that allows Java-based applications (applets) to be run securely on smart cards and similar small memory footprint devices. Java Card is the tiniest of Java platforms targeted for embedded devices.

Rob

Great article, and looking forward to the next one about HSM, KMS, and secure enclaves! (Are you familiar with Fortanix SDKMS, which combines all of these?)

leave a comment...