User authentication with passwords, What’s SRP? posted May 2020

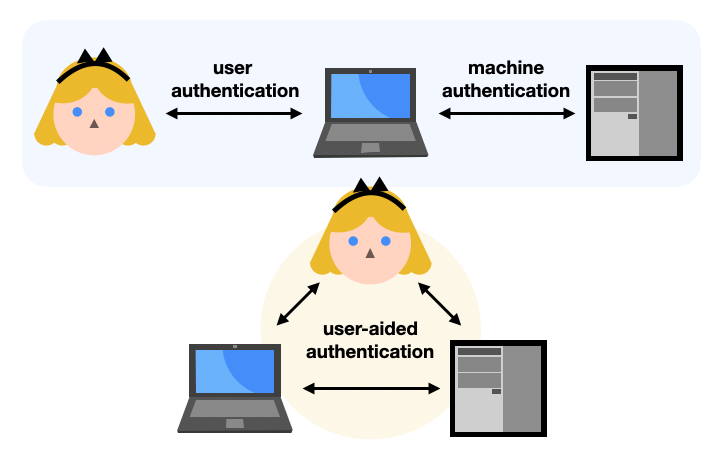

The Secure Remote Password (SRP) protocol is first and foremost a Password Authenticated Key Exchange (PAKE). Specifically, SRP is an asymmetric or augmented PAKE: it’s a key exchange where only one side is authenticated thanks to a password. This is usually useful for user authentication protocols. Theoretically any client-server protocol that relies on passwords (like SSH) could be doing it, but instead such protocols often have the password directly sent to the server (hopefully on a secure connection). As such, asymmetric PAKEs offer an interesting way to augment user authentication protocols to avoid the server learning about the user’s password.

Note that the other type of PAKE is called a symmetric or balanced PAKE. In a symmetric PAKE two sides are authenticated thanks to the same password. This is usually useful in user-aided authentication protocols where a user attempts to pair two physical devices together, for example a mobile phone or laptop to a WiFi router. (Note that the recent WiFi protocol WPA3 uses the DragonFly symmetric PAKE for this.)

In this blog post I will answer the following questions:

- What is SRP?

- How does SRP work?

- Should I use SRP today?

What is SRP?

The stanford SRP homepage puts it in these words:

The Secure Remote Password protocol performs secure remote authentication of short human-memorizable passwords and resists both passive and active network attacks. Because SRP offers this unique combination of password security, user convenience, and freedom from restrictive licenses, it is the most widely standardized protocol of its type, and as a result is being used by organizations both large and small, commercial and open-source, to secure nearly every type of human-authenticated network traffic on a variety of computing platforms.

and goes on to say:

The SRP ciphersuites have become established as the solution for secure mutual password authentication in SSL/TLS, solving the common problem of establishing a secure communications session based on a human-memorized password in a way that is crytographically sound, standardized, peer-reviewed, and has multiple interoperating implementations. As with any crypto primitive, it is almost always better to reuse an existing well-tested package than to start from scratch.

But the Stanford SRP homepage seems to date from the late 90s.

SRP was standardized for the first time in 2000 in RFC 2944 - Telnet Authentication: SRP. Nowadays, most people refer to SRP as the implementation used in TLS. This one was specified in 2007 in RFC 5054 - Using the Secure Remote Password (SRP) Protocol for TLS Authentication.

How does SRP work?

The Stanford SRP homage lists 4 different versions of SRP, with the last one being SRP 6. Not sure where version 4 and 5 are, but version 6 is the version that is standardized and implemented in TLS. There is also the revision SRP 6a, but I’m also not sure if it’s in use anywhere today.

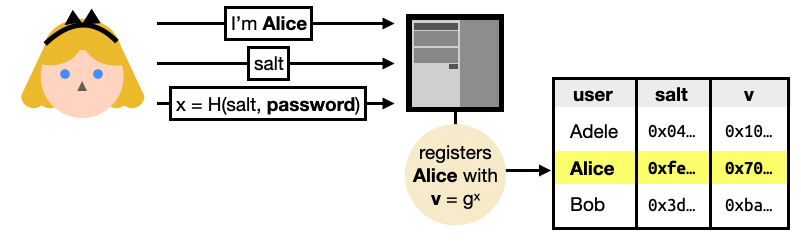

To register, Alice sends her identity, a random $salt$, and a salted hash $x$ of her password. Right from the start, you can see that a hash function is used (instead of a password hash function like Argon2) and thus anyone who sees this message can efficiently brute-force the hashed password. Not great. The use of the user-generated salt though, manage to prevent brute-force attacks that would impact all users.

The server can then register Alice by exponentiating a generator of a pre-determined ring (an additive group with a multiplicative operation) with the hashed password. This is an important step as you will see that anyone with the knowledge of $x$ can impersonate Alice.

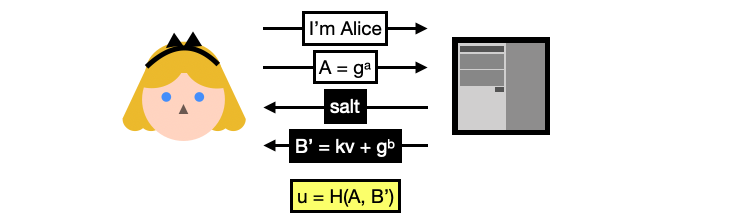

What follows is the login protocol:

You can now see why this is called a password authenticated key exchange, the login flow includes the standard ephemeral key exchange with a twist: the server’s public key $B’$ is blinded or hidden with $v$, a random value derived from Alice’s password. (Note here $k$ is a constant fixed by the protocol so we will just ignore it.)

Alice can only unblinds the server’s ephemeral key by deriving $v$ herself. To do this, she needs the $salt$ she registered with (and this is why the server sends it back to Alice as part of the flow). For Alice, the SRP login flow goes like this:

- Alice re-computes $x = H(salt, password)$ using her password and the salt received from the server.

- Alice unblinds the server’s ephemeral key by doing $B=B’- kg^x = g^b$

- Alice then computes the shared secret $S$ by multiplying the results of two key exchanges:

- $B^a$, the ephemeral key exchange

- $B^{ux}$, a key exchange between the server’s public key and a value combining the hashed password and the two ephemeral public keys

Interestingly, the second key exchange makes sure that the hashed password and the transcript gets involved in the computation of the shared secret. But strangely, only the public keys and not the full transcript are used.

The server can then compute the shared secret $S$ as well, using the multiplication of the same two key exchanges:

- $A^b$, the ephemeral key exchange

- $v^{ub}$, the other key exchange involving the hashed password and the two ephemeral public keys

The final step is for both sides to hash the shared secret and use it as the session key $K = H(S)$. Key confirmation can then happen after both sides make successful use of this session key. (Without key confirmation, you’re not sure if the other side managed to perform the PAKE.)

Should I use SRP today?

The SRP scheme is a much better way to handle user passwords, but it has a number of flaws that make the PAKE protocol less than ideal. For example, someone who intercepts the registration process can then easily impersonate Alice as the password is never directly used in the protocol, but instead the salted hash of the password which is communicated during the registration process.

This was noticed by multiple security researchers along the years. Matthew Green in 2018 wrote Should you use SRP?, in which he says:

Lest you think these positive results are all by design, I would note that there are [five prior versions] of the SRP protocol, each of which contains vulnerabilities. So the current status seems to have arrived through a process of attrition, more than design.

After noting that the combination of multiplication and addition makes it impossible to implement in elliptic curve groups, Matthew Green concludes with:

In summary, SRP is just weird. It was created in 1998 and bears all the marks of a protocol invented in the prehistoric days of crypto. It’s been repeatedly broken in various ways, though the most recent [v6] revision doesn’t seem obviously busted — as long as you implement it carefully and use the right parameters. It has no security proof worth a damn, though some will say this doesn’t matter (I disagree with them.)

Furthermore, SRP is not available in the last version of TLS (TLS 1.3).

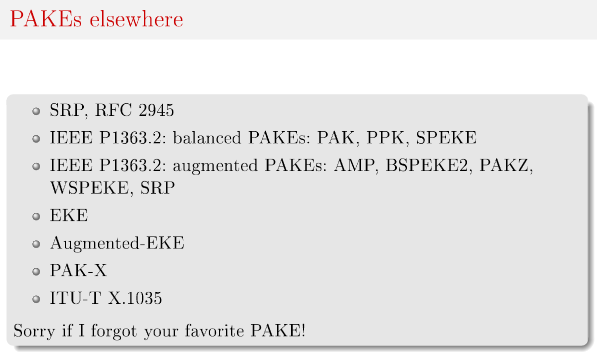

Since then, many schemes have been proposed, and even standardized and productionized (for example PAK was standardized by Google in 2010) The IETF 104, March 2019 - Overview of existing PAKEs and PAKE selection criteria has a list:

In the summer of 2019, the Crypto Forum Research Group (CFRG) of the IETF started a PAKE selection process, with goal to pick one algorithm to standardize for each category of PAKEs (symmetric/balanced and asymmetric/augmented):

Two months ago (March 20th, 2020) the CFRG announced the end of the PAKE selection process, selecting:

- CPace as the symmetric/balanced PAKE (from Björn Haase and Benoît Labrique)

- OPAQUE as the asymmetric/augmented PAKE (from Stanislaw Jarecki, Hugo Krawczyk, and Jiayu Xu)

Thus, my recommendation is simple, today you should use OPAQUE!

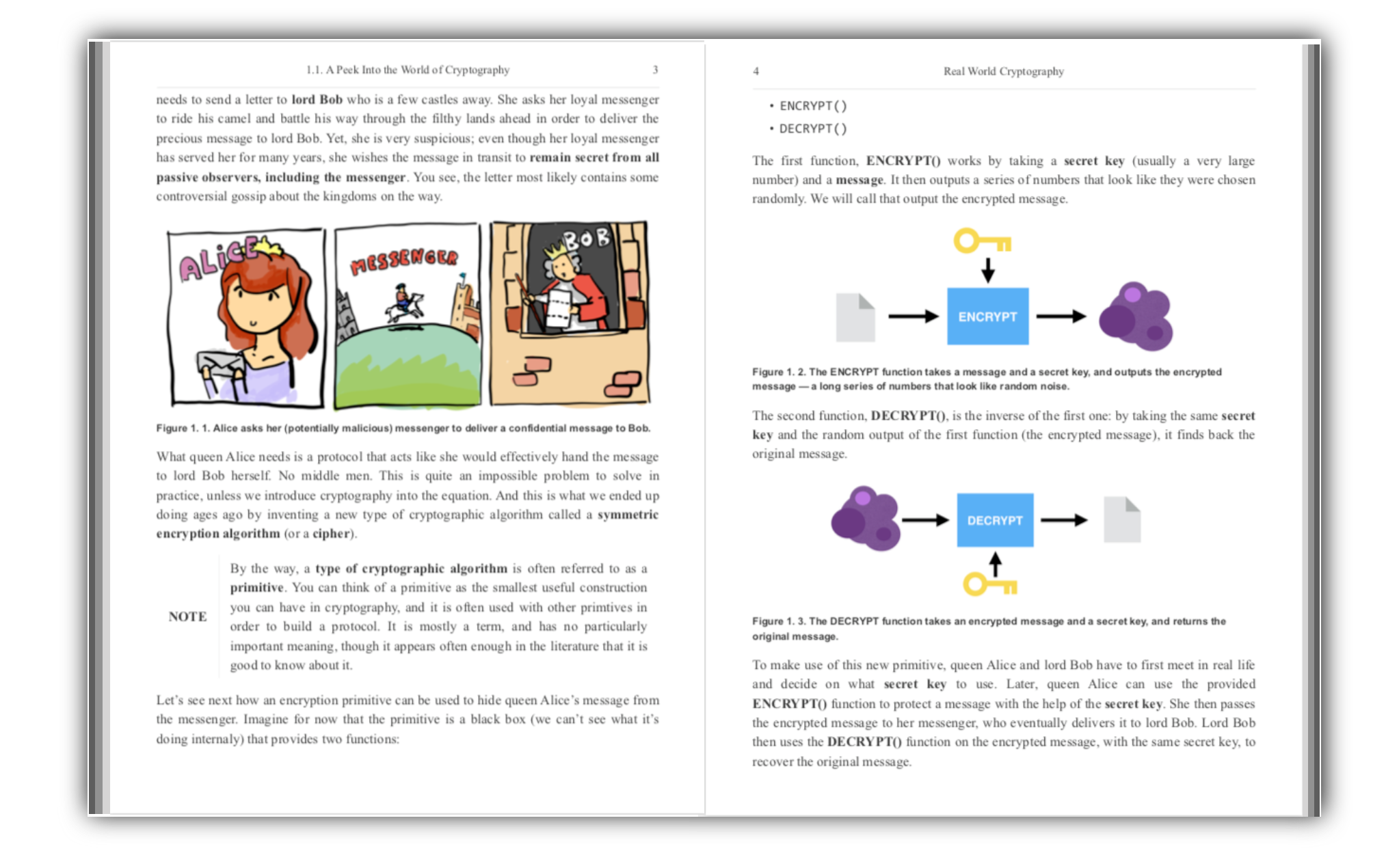

If you want to learn more about OPAQUE, check out chapter 11 of my book real world cryptography.

Comments

mat

Why does Alice even send x during the registration and not just g^x?

david

They actually do, looking at the webpage this is not detailed but the paper details this!

John

Trust free secure registration is an oxymoron.

leave a comment...