Quick access to articles on this page:

more on the next page...

BLS is a digital signature scheme being standardized.

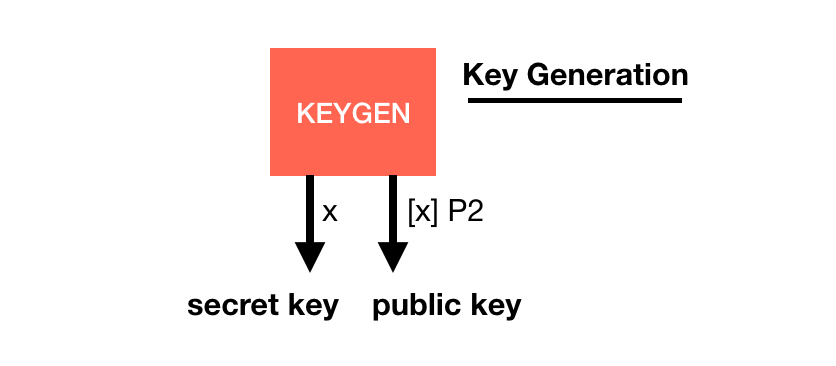

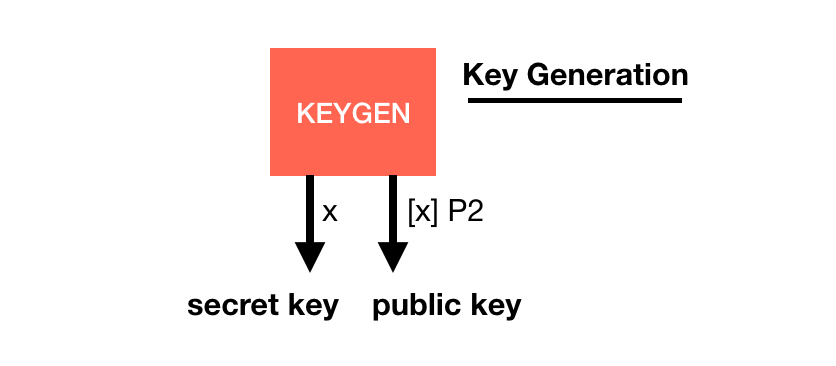

Its basis is quite similar to other signature schemes, it has a key generation with a generator $P2$:

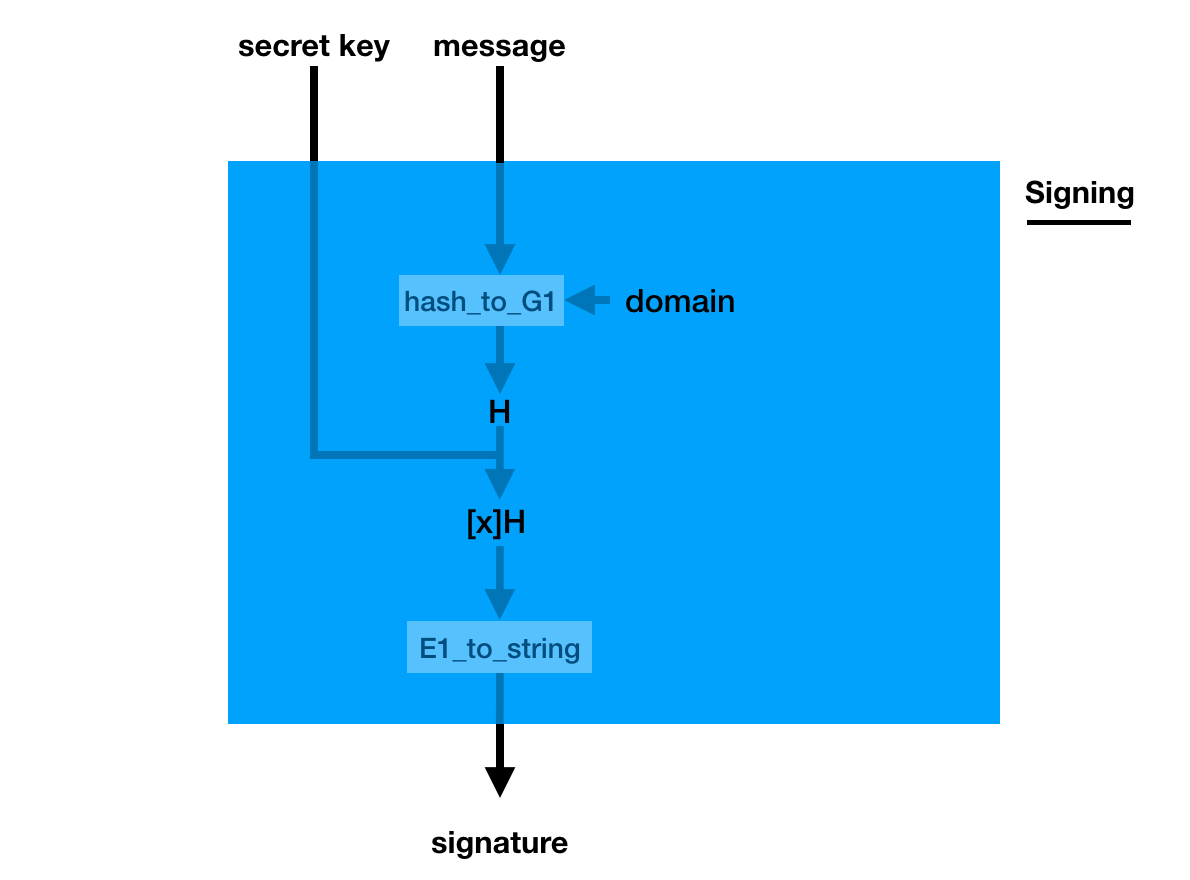

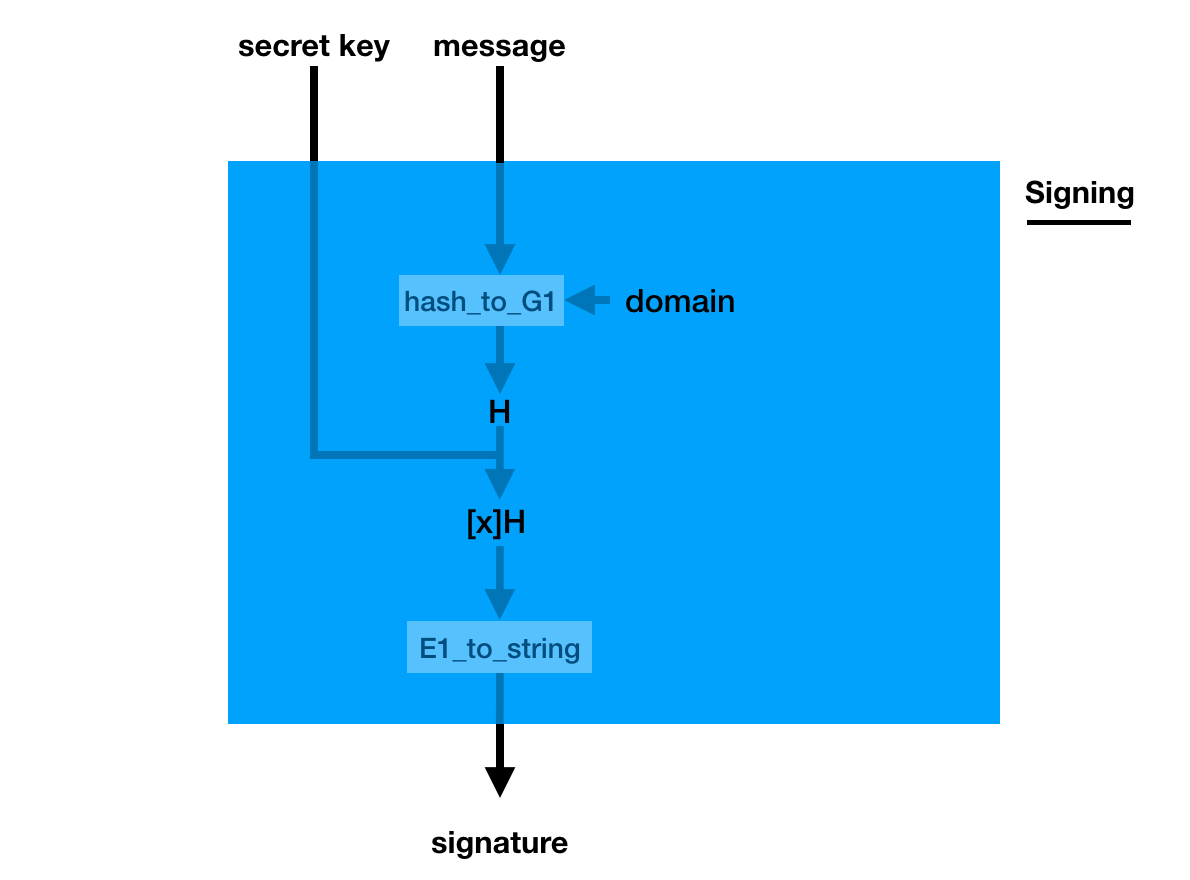

The signature is a bit weird though, you pretend the hashed message is the generator (using a hash_to_G1 function you hash the message into a point on a curve) and you do what you usually do in a key generation: you make it a public key with your private key

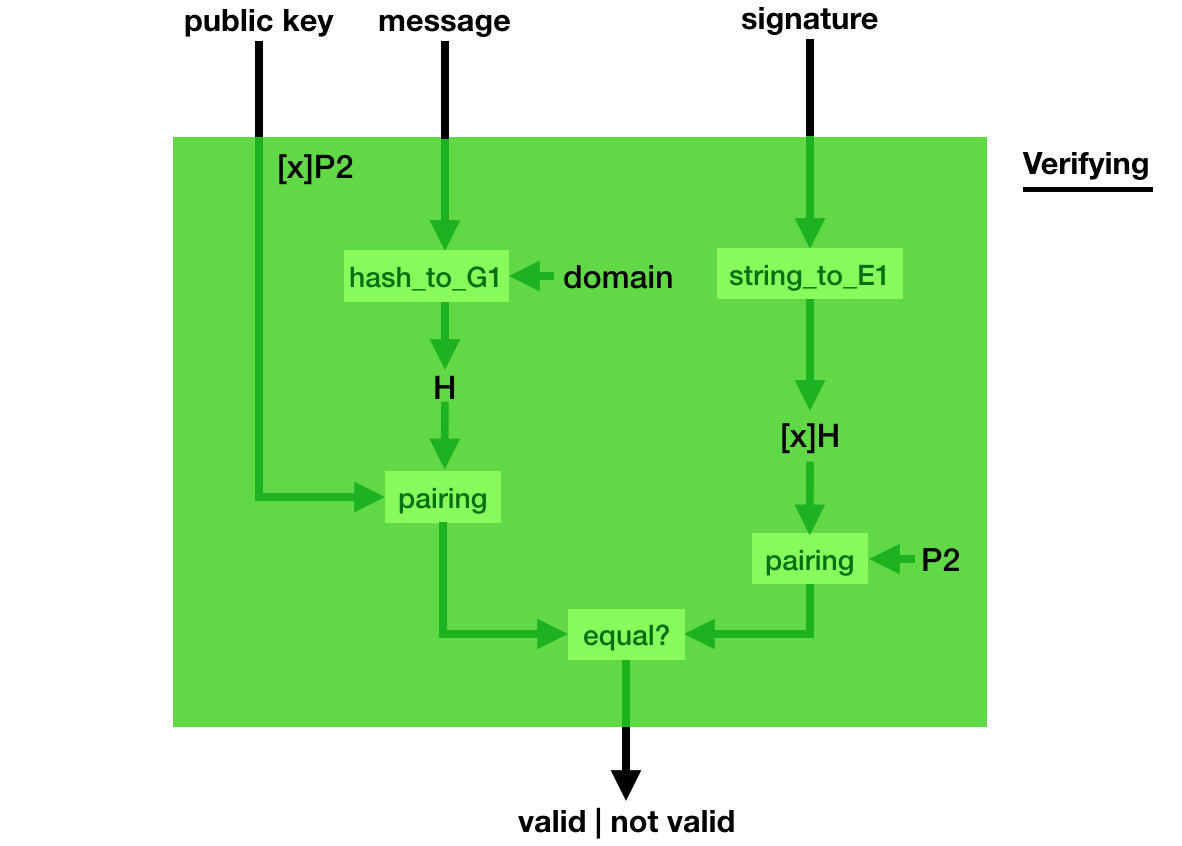

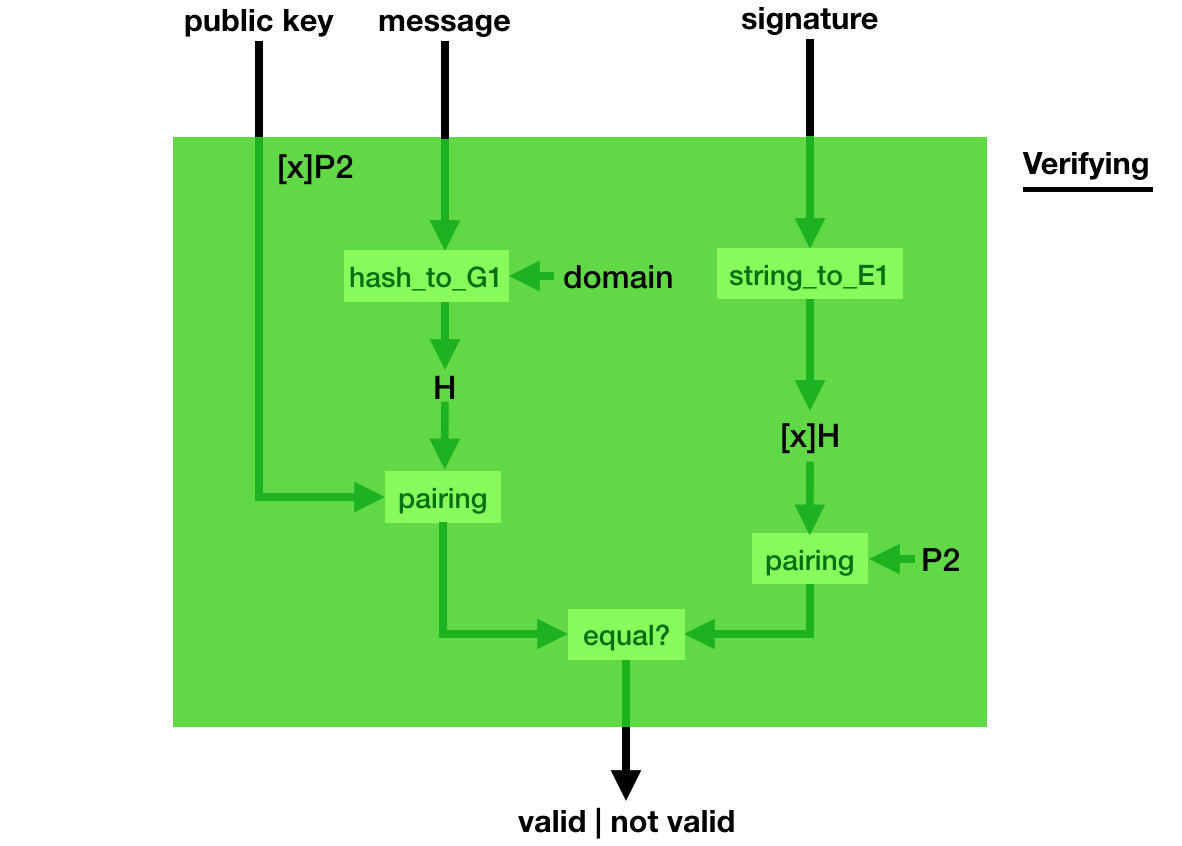

Verification is even weirder, you use a bilinear pairing to verify that indeed, pairing([secret_key]hashed_msg, P2) = pairing([secret_key]P2, hashed_msg).

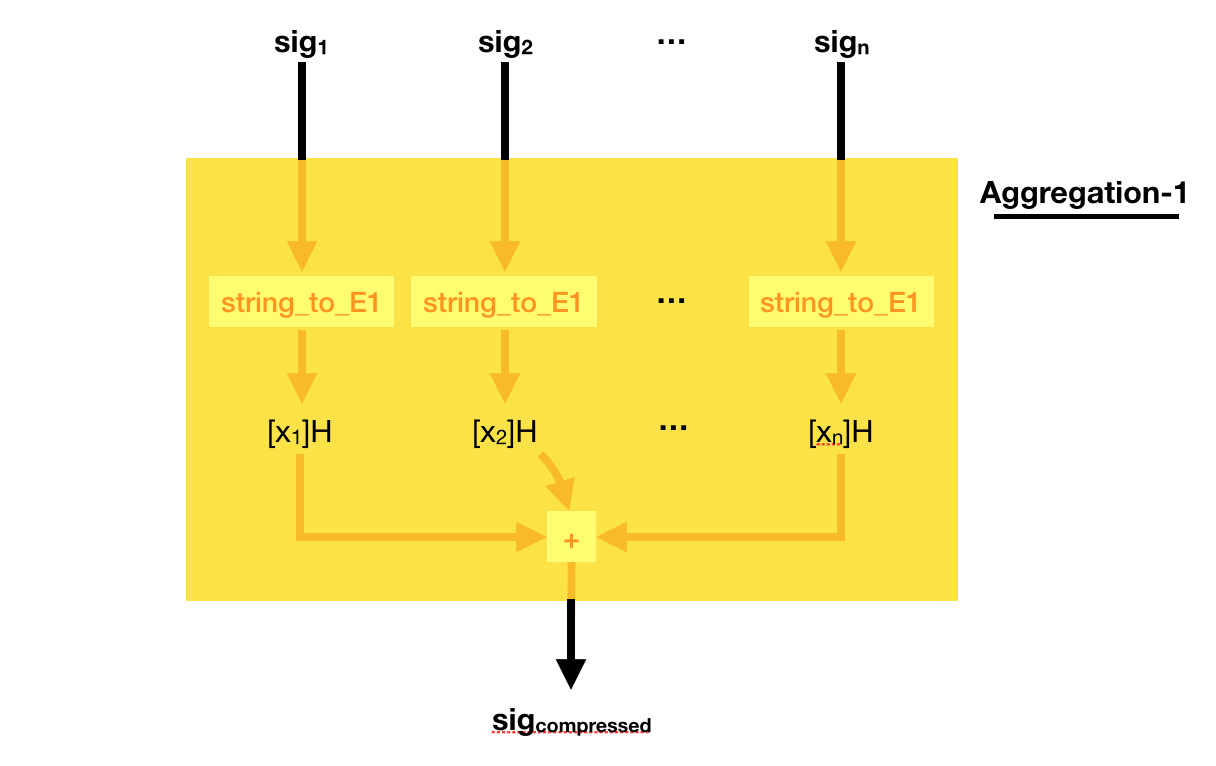

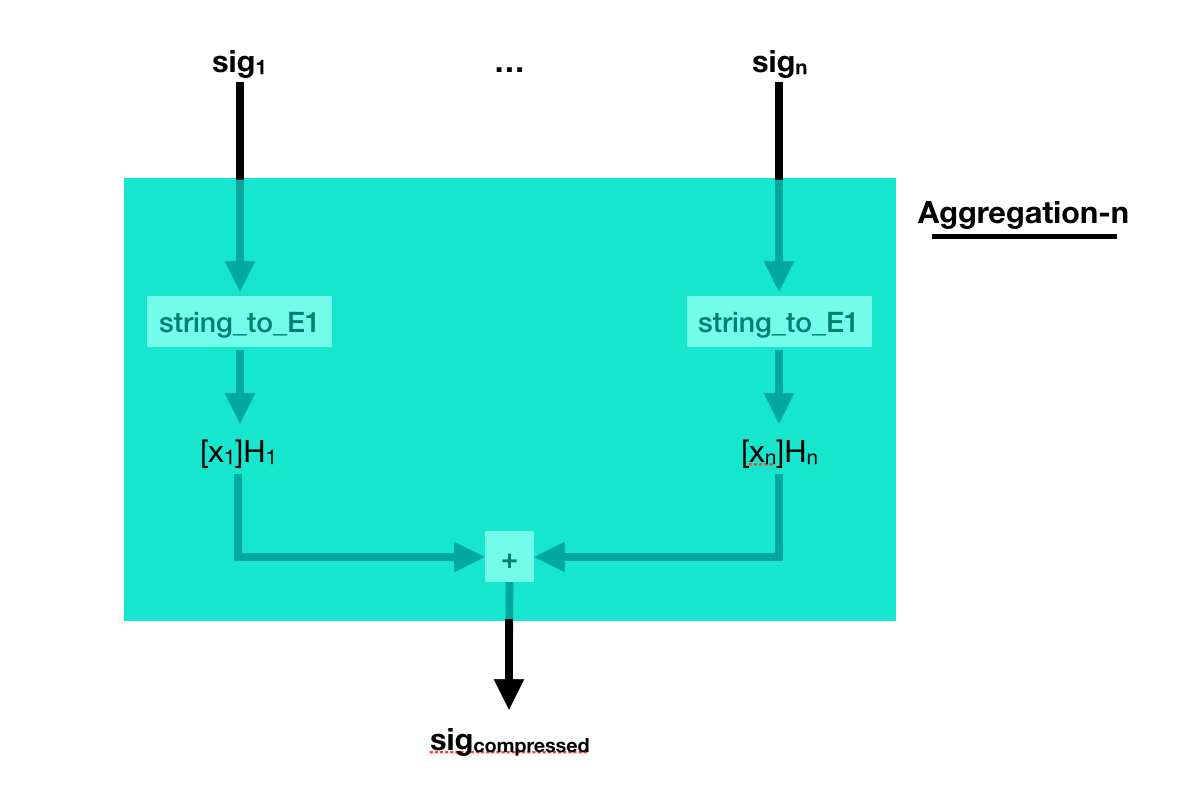

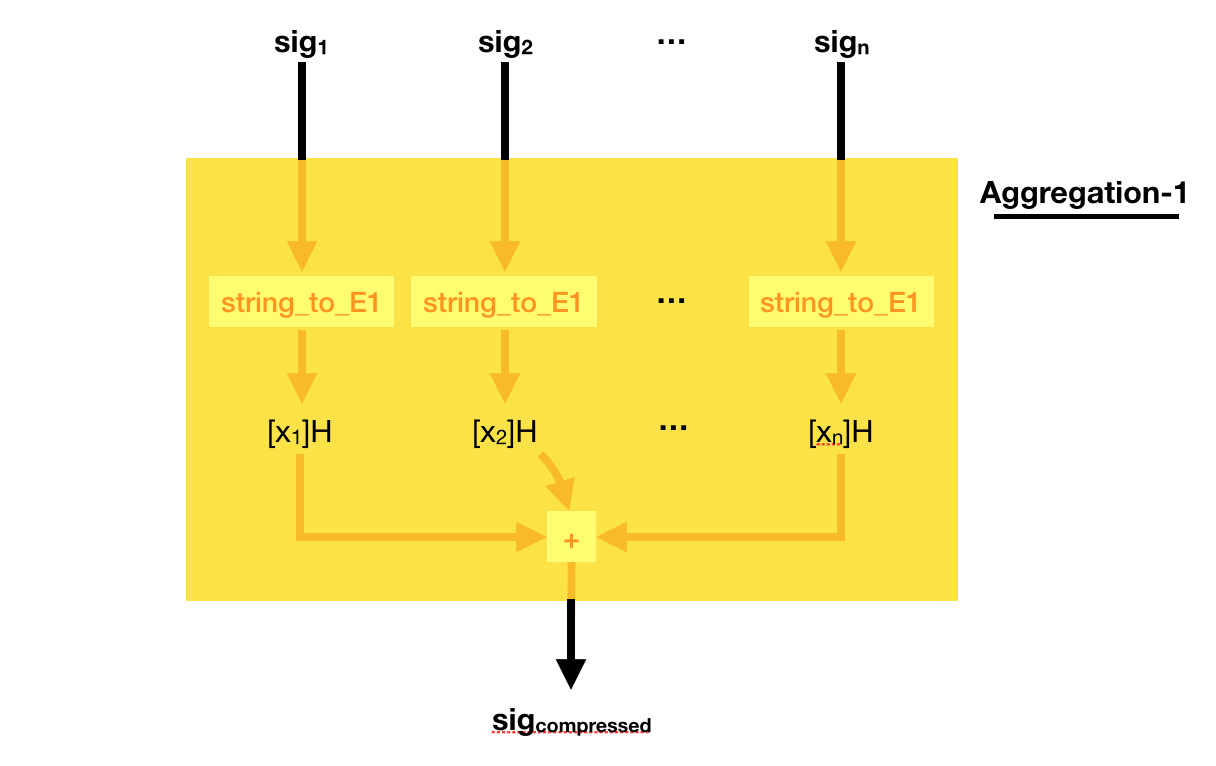

This weird signing/verifying process allows for pretty cool stuff. You can compress (aggregate) signatures of the same msg in a single signature!

To do that, simply add all the signatures together! Easy peasy right?

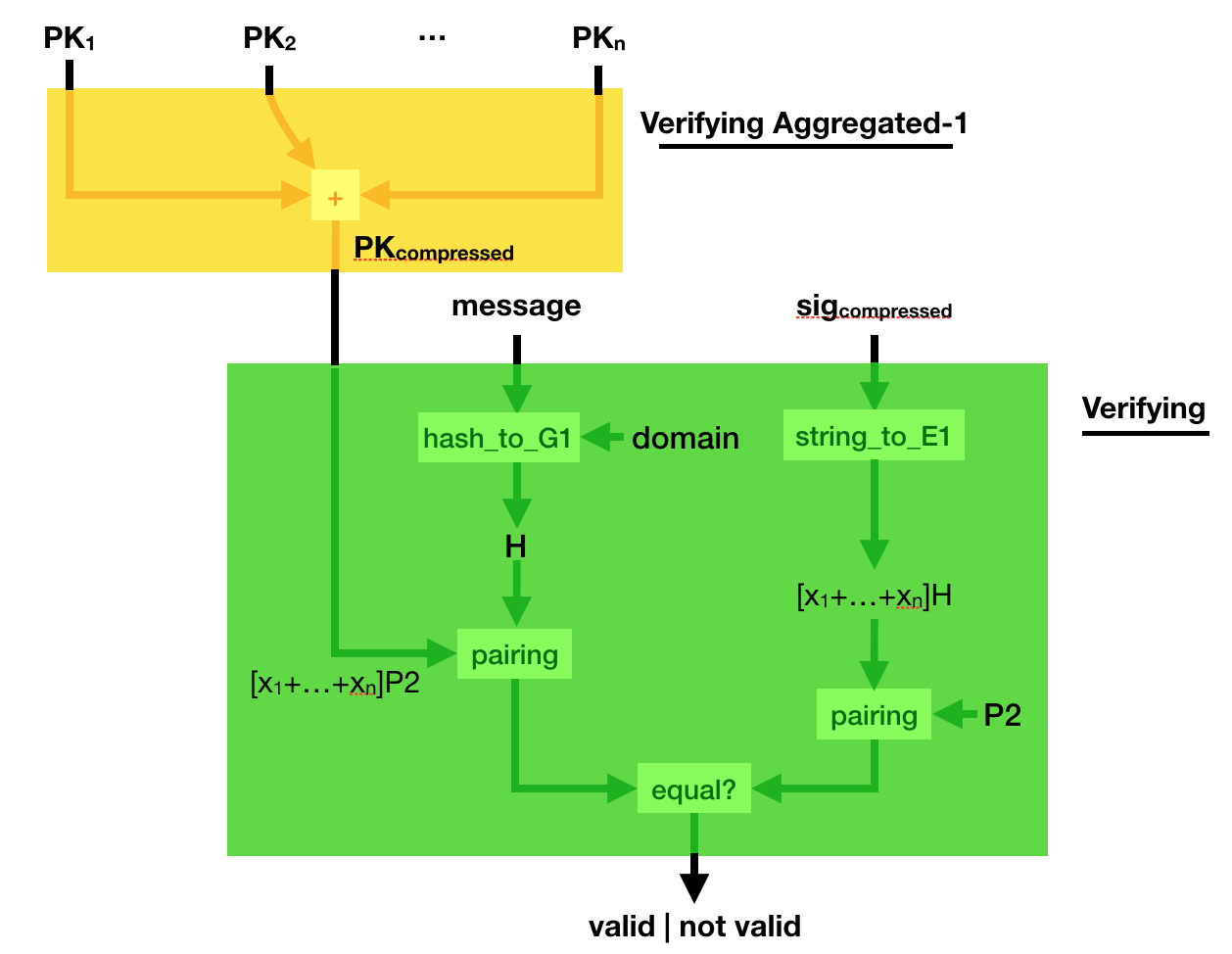

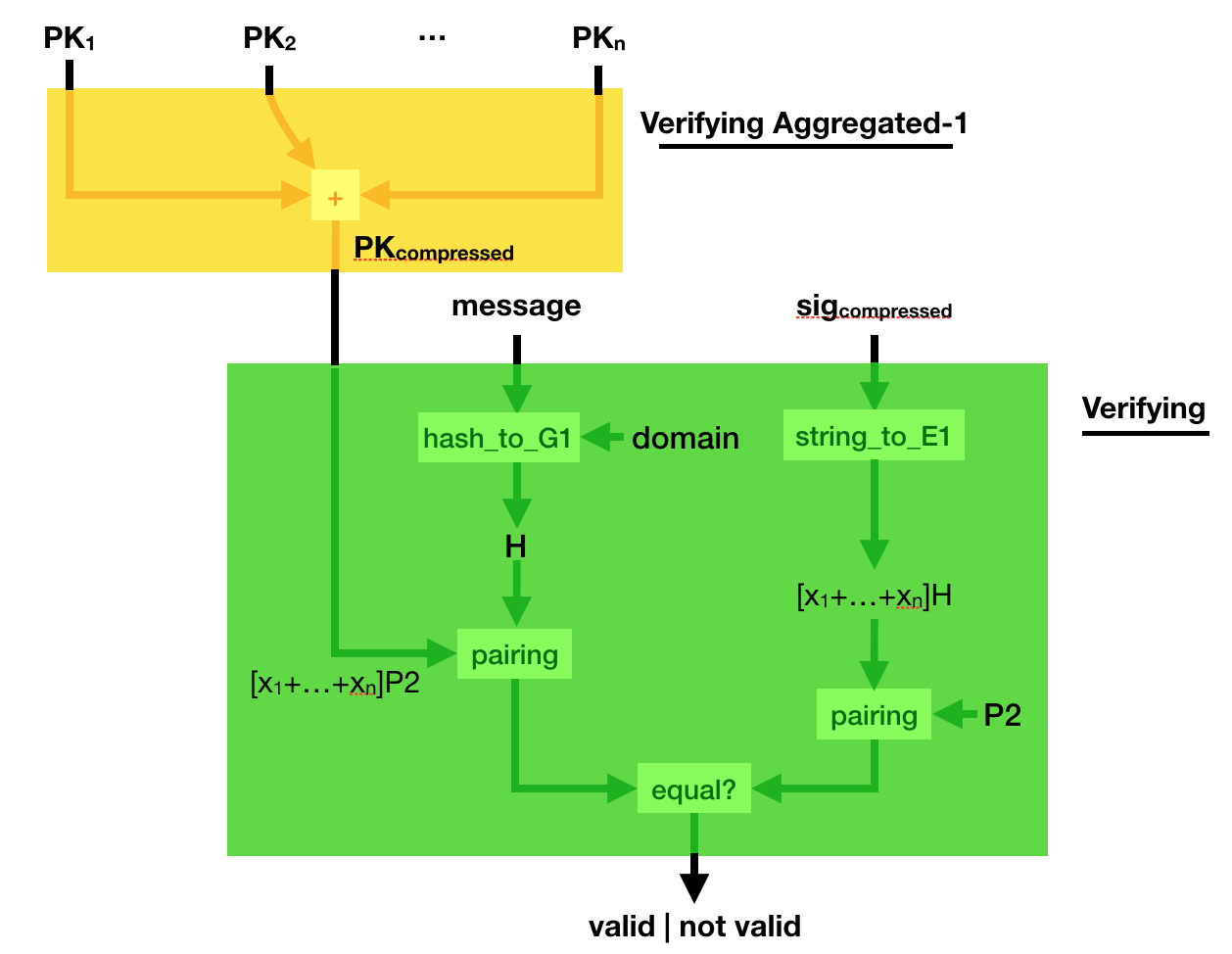

Can you verify such a compressed signature? Yes you can.

Simply compress the public key, the same way you compressed the signature. And verify the sig_compressed with the public_key_compressed. Elegant :)

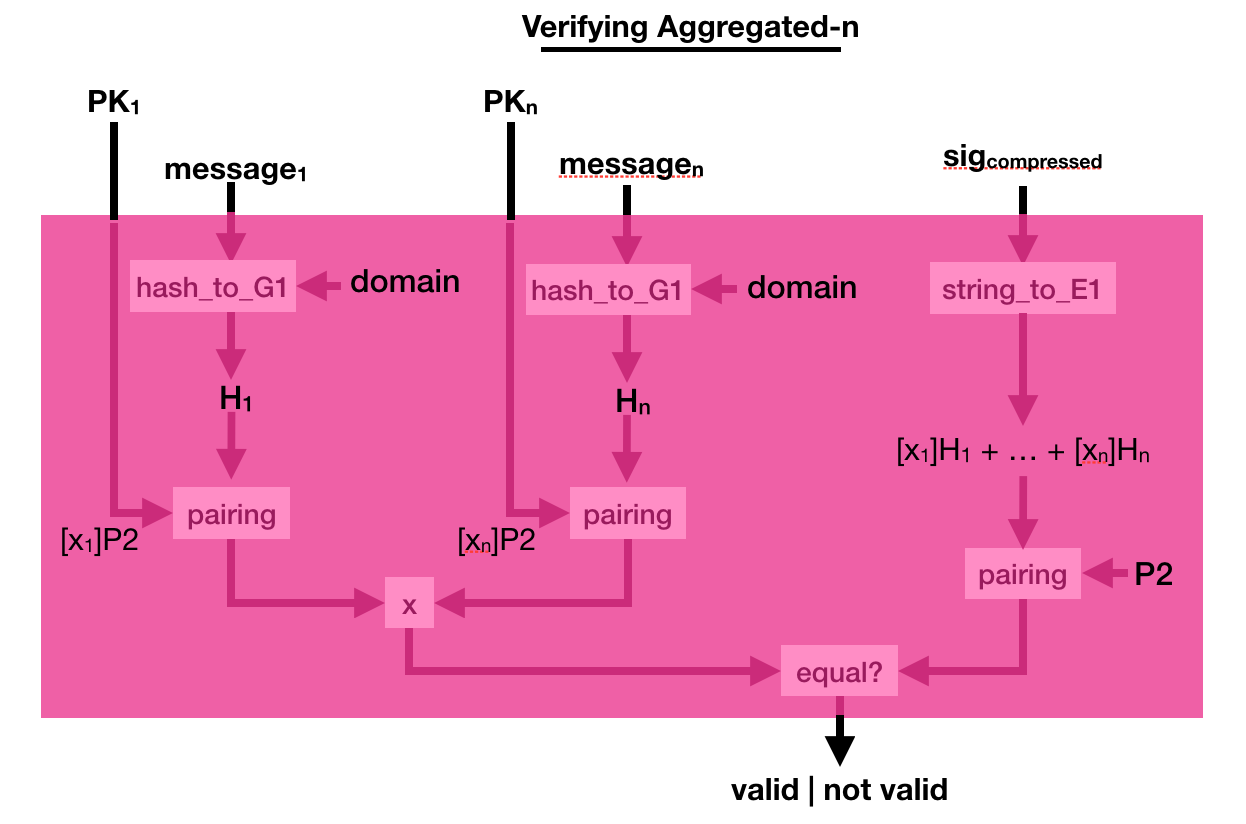

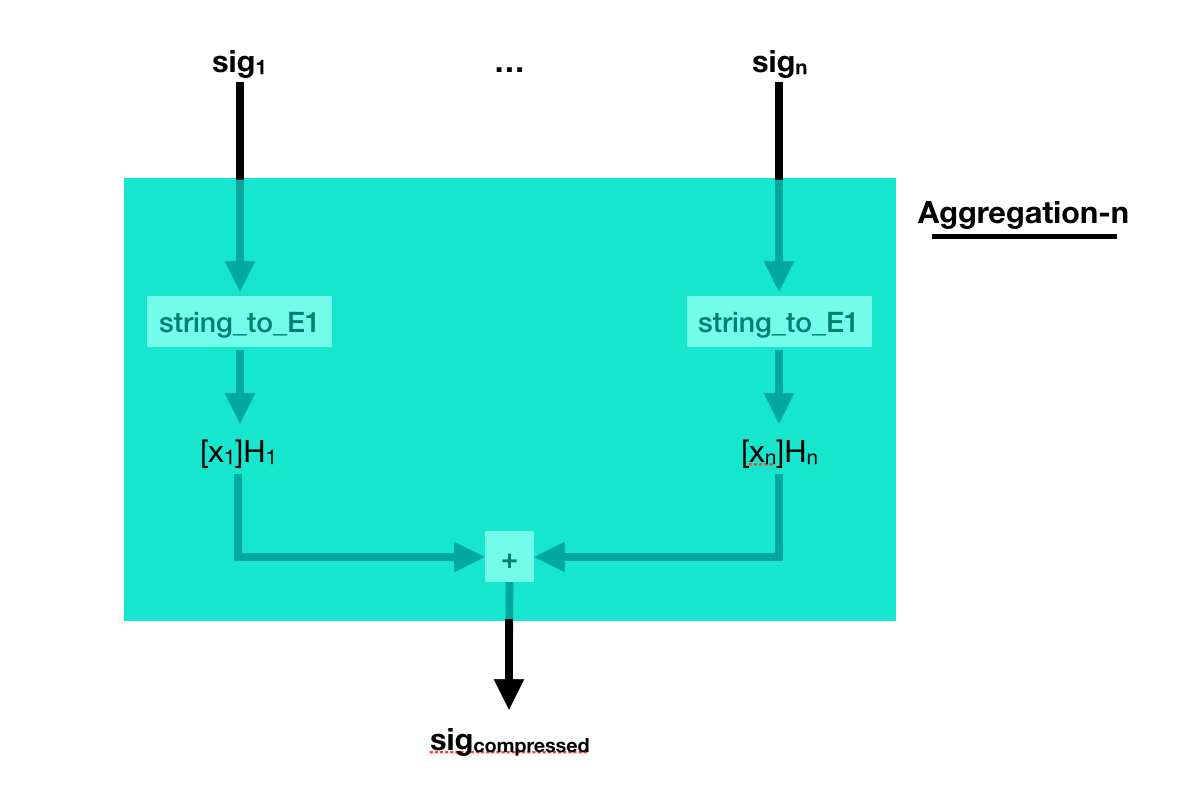

But what if the different signatures are on different messages? Well, just add them together as well.

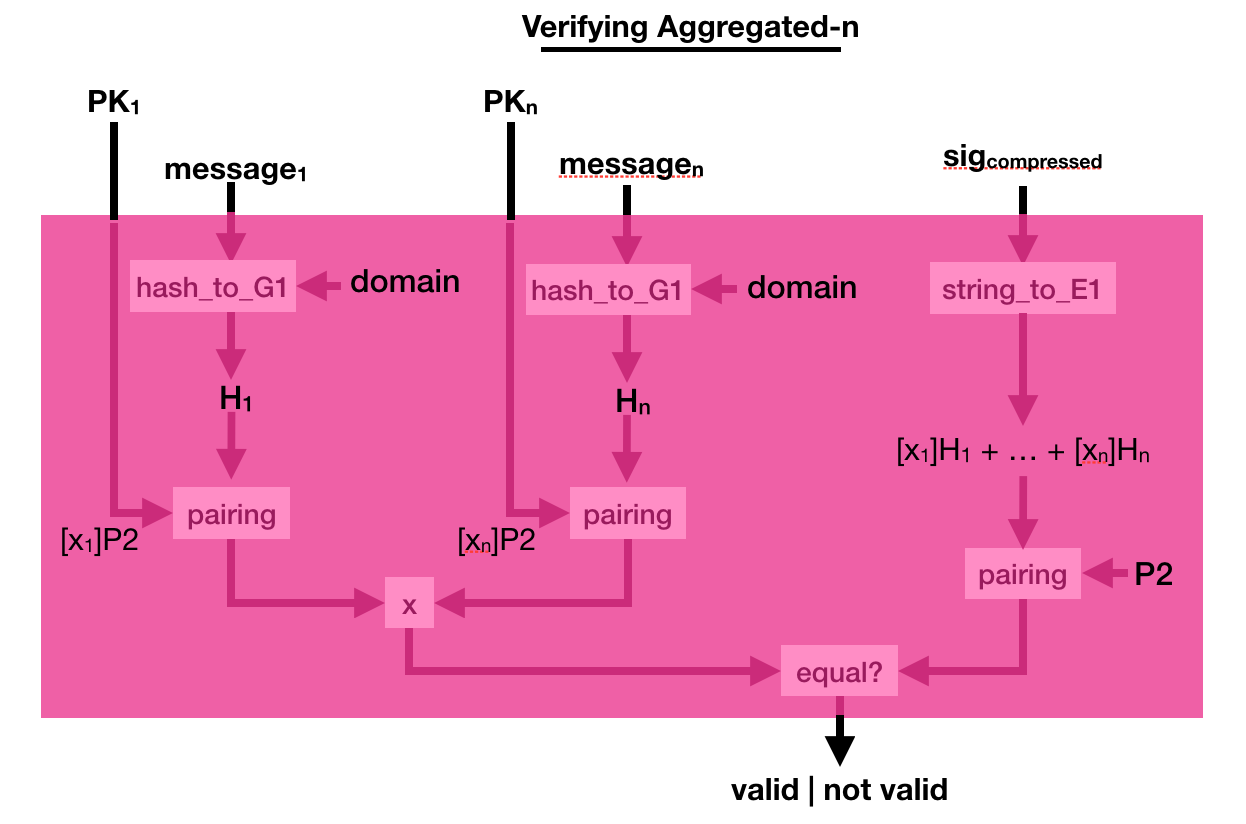

The process to verify that is a bit more complicated. This time you multiply a bunch of pairing([secret_key]P2, hashed_msg) together, and you verify that it is equal to another pairing made out of the compressed signature. Pairings are magical!

A paper on (attacking) database encryption was just released by Paul Grubbs, Marie-Sarah Lacharite, Brice Minaud, and Kenneth G. Paterson. Matthew Green just posted an article about it. I don't know much about database encryption, but from my experience there is a lot of solutions and it is quite hard to understand what you're getting from them. So I really like this kind of articles. I figured I would add my 2 cents to encourage people to write about database encryption.

Anonymity

I want to mention this first, because this is one of the most stupid solution I've seen being used to either anonymize a database or protect it. What you do is that you keep track of a mapping between real words and random words. For example "pasta" means "female" and "guitar" means "male". Then you replace all these words by their counterparts (so all the mention of "female" in your database get replaced by "pasta"). This allow you to have a database that doesn't hold any information. In practice, this is leaking way too much and it is in no way a good idea. It is called tokenization.

Database Breaches

Databases contain user information, like credit card numbers and passwords. They are often the target of attacks, as you can read in the news. For example, you can check on haveibeenpwned.com if your email has been part of a database breach. A friend of mine has been part of 19 database breaches apparently.

To prevent such things from happening, on the server side, you can encrypt your database.

Why not, after all.

The easier way to do this is to use Transparent Database Encryption (TDE) which a bunch of database engine ship by default. It's really simple, some columns in tables are encrypted with a key. The id and the table name are probably used to generate the nonce, and there's probably some authentication of the row or something so that rows can't be swapped. If your database engine doesn't support TDE, people will use home-made solutions like sqlcipher. The problem with TDE or sqlcipher, is that the key is just lying around next to your database. In practice, this seems to be good enough to get compliant to regulation stuff (perhaps like FIPS and PCI-DSS).

This is also often enough to defend against a lot of attacks, which are often just dumb smash-and-grab attacks where the attacker dumps the database and flees the crime scene right away. If the attacker is not in a hurry though, he can look around and find the key.

It's not that hard.

EDIT: one of the not so great thing about this kind of solution, is that the database is not really searchable unless you left some fields unencrypted. If you don't do searches, it's fine, but if you do, it's not so fine. The other solutions I talk about in this post also try to provide searchable encryption. They belong in the field of Searchable Symmetric Encryption (SSE).

Untrusted Databases

The solution here is to segment your architecture into two parts, a client who holds the key and an untrusted database. If the database is breached, then the attacker learns nothing.

I hope you are starting to realize that this solution is really about defense in depth, we're just moving the security somewhere else.

If both sides are breached, it's game over, if the client is breached an attacker can also start making whatever requests it wants. The database might be rate-limited, but it won't stop slow attacks. For password hashing, there have been hilarious proposals to solve this with security through obesity, and more serious proposals to solve this with password hashing delegation (see PASS or makwa).

But yeah, remember, this is defense in depth. Not that defense in depth doesn't work, but you have to frame your research in that perspective, and you also have to consider that whatever you do, the more annoying it is and the more efficient it will be at preventing most attacks.

Optimizations

Now that we got the setup out of the way, how do we implement that?

The naive approach is to encrypt everything client-side. But this is awful when you want to do complicated queries, because the server has to pretty much send you the entire database for you to decrypt it and query it yourself. There were some improvements known there, but there is only so much you can probably do.

Other solutions (cryptdb, mylar, opaque, preveil, verena, etc.) use a mix of cryptography (layers of encryption, homomorphic encryption, order preserving encryption, order revealing encryption, etc.) and perhaps even hardware solutions (Intel SGX) to solve the efficiency issue.

Unfortunately, most of these schemes are not clear about the threat model. As they do not use the naive approach, they have to leak some amount of information, and it is not obvious what attacks can do. And actually, if you read the research done on the subject, it seems like they could in practice leak a lot more than what we would expect. Some researchers are very angry, and claim that the situation is worst than having a plaintext database due to do the illusion of security when using such database encryption solutions.

Is there no good solution?

In practice, fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) could work to prevent the bad leakage we talked about. I don't know enough about it, but I know that there is no CCA2-secure FHE algorithm, which might be an issue. The other, more glaring, issue is that FHE is slow as hell. It could be practical in some situations, but probably not at scale and for this particular problem. For more constrained types of queries, somewhat homomorphic encryption (SHE) should be faster, but is it practical? Partial homomorphic encryption (HE) is fast but limited. The paillier cryptosystem, an HE algorithm, is actually used in cryptdb to do addition on ciphertexts.

Conclusion

The take away is that database encryption is about defense in depth. Which means it is useful, but it is not bullet proof. Just be aware of that.

Along the years, I've been influenced by many great minds on how to do research. I thought I would paste a few of their advice here.

Disregard.

That advice from Feynman’s Breakthrough, Disregard Others!

was really useful to me as I realized that I HAD to miss out on what was happening around me if I wanted to do research. It's quite hard nowadays, with all the noise and all the cool stuff happening, to focus on one's work. But it seems like Feynman had the same issues even before the internet was born. So that's one of the secret: JOMO it out (Joy Of Missing Out).

The word was “Disregard!”

“That’s what I’d forgotten!” he shouted (in the middle of the night). “You have to worry about your own work and ignore what everyone else is doing.” At first light, he called his wife, Gweneth, and said, “I think I’ve figured it out. Now I’ll be able to work again!” […]

Reading Papers.

That advice comes from Andrew Ng's interview:

"I don’t know how the human brain works but it’s almost magical: when you read enough or talk to enough experts, when you have enough inputs, new ideas start appearing."

and indeed. I've noticed that, after reading a bunch of papers, new ideas usually pop in my head and I'm able to do some new research. It actually seems like it is the only way.

Dedication.

Richard Hamming in "You and Your Research" wrote several good advice:

Let me start not logically, but psychologically. I find that the major objection is that people think great science is done by luck. It's all a matter of luck. Well, consider Einstein. Note how many different things he did that were good. Was it all luck? Wasn't it a little too repetitive? Consider Shannon. He didn't do just information theory. Several years before, he did some other good things and some which are still locked up in the security of cryptography. He did many good things.

You see again and again, that it is more than one thing from a good person. Once in a while a person does only one thing in his whole life, and we'll talk about that later, but a lot of times there is repetition. I claim that luck will not cover everything. And I will cite Pasteur who said, ``Luck favors the prepared mind.'' And I think that says it the way I believe it. There is indeed an element of luck, and no, there isn't. The prepared mind sooner or later finds something important and does it. So yes, it is luck. The particular thing you do is luck, but that you do something is not.

Sam Altman wrote "compound yourself" the other day, which reflects what Hamming was saying as well when quoting Bode:

What Bode was saying was this: ``Knowledge and productivity are like compound interest.'' Given two people of approximately the same ability and one person who works ten percent more than the other, the latter will more than twice outproduce the former. The more you know, the more you learn; the more you learn, the more you can do; the more you can do, the more the opportunity - it is very much like compound interest

Mental State.

Here's some quote about being in the right state of mind. From Hamming again. The first one rings true to me as I gained much more confidence in doing research after releasing a few papers and being cited.

One success brought him confidence and courage

The second one is quite impactful as well, as trains, planes and hotels without wifi are often my most productive places to work from:

What most people think are the best working conditions, are not. Very clearly they are not because people are often most productive when working conditions are bad

It even sounds like prison, yes prison, is sometimes cited as the best place to do one's work! This is an extract of a letter from André Weil after having spent some time in Rouen's prison:

My mathematics work is proceeding beyond my wildest hopes, and I am even a bit worried - if it's only in prison that I work so well, will I have to arrange to spend two or three months locked up every year?

And if you can't believe this, here's what Reddit has to say about it:

Just spent four months in jail. I read over thirty books and I feel like I’ve been born again.

Important Problems.

Hamming again, on working on important problems:

And I started asking, "What are the important problems of your field?" And after a week or so, "What important problems are you working on?"

If you do not work on an important problem, it's unlikely you'll do important work. It's perfectly obvious. Great scientists have thought through, in a careful way, a number of important problems in their field, and they keep an eye on wondering how to attack them

I noticed the following facts about people who work with the door open or the door closed. I notice that if you have the door to your office closed, you get more work done today and tomorrow, and you are more productive than most. But 10 years later somehow you don't know quite know what problems are worth working on; all the hard work you do is sort of tangential in importance. He who works with the door open gets all kinds of interruptions, but he also occasionally gets clues as to what the world is and what might be important.

One's limitations.

Silvio Micali gave a talk in which the last 10 minutes (which I linked) were a collection of advice for young researchers. It's quite fun to watch and emphasizes that one must be stubborn to go through with one's research. He also mentions being fine with one's limitations:

Our limitation is our strength. Because of your limitation you are forced to approach a problem differently.

Maker's schedule.

Paul Graham wrote "Maker's schedule, manager's schedule" which differentiates the kind of work schedule one can have:

When you're operating on the maker's schedule, meetings are a disaster. A single meeting can blow a whole afternoon, by breaking it into two pieces each too small to do anything hard in. Plus you have to remember to go to the meeting. That's no problem for someone on the manager's schedule. There's always something coming on the next hour; the only question is what. But when someone on the maker's schedule has a meeting, they have to think about it.

This is something Hamming touched as well, but more on the personal life plan:

"I don't like to say it in front of my wife, but I did sort of neglect her sometimes; I needed to study. You have to neglect things if you intend to get what you want done. There's no question about this."

Deadlines.

I can't remember where I read that, but someone was saying that deadlines were great, and that he/she was often promising things to people in order to get things done. The idea was that if you break your promise, you lose integrity and shame rains upon you. So that's some sort of self-fabricated pressure.

More?

If you know more cool articles and videos like that, please share :)

At Real World Crypto 2019, Mihir Bellare won the Levchin Prize (along with Eric Rescorla) and gave a short and inspiring speech. You can watch it here. In it, he briefly mentioned what I'll call the speed issue:

when I started it was a question of being responsive to the industry and practical needs [...] Now I think these are much deeper questions [...] Who benefits from the work we do? [...] Who benefits from making things faster beyond a certain point? The constant search for speed. What sort of people do we become when we cannot wait half a second for a web page to load because TLS is doing a round trip and we're cutting corners.

In here, Bellare is obviously hinting at Eric Rescorla's work with TLS 1.3, in particular the 0-RTT or early data feature of the new protocol. If you don't know what it is, it's a new feature which allows a client to send encrypted data as part of its very first flight of messages. As I explained in this video, it does not protect against replay attacks, nor benefits from forward secrecy.

Replay: a passive observer can record these specific messages, then replay them at a later point in time. You can imagine that if the messages were bank transactions, and replaying them would prompt the bank to initiate a new transaction, then that would be a problem.

Forward Secrecy: TLS sessions in TLS 1.3 benefits from this security property by default. If the server's long-term keys are stolen at a certain point in time, previous sessions won't be decryptable. This is because each session's security is augmented by doing an ephemeral key exchange with keys that are deleted right after the handshake. To break such a session you would need to obtain these ephemeral keys in addition to the long-term key of the server. Sending 0-RTT data happens before any ephemeral key exchange can happen. The data is simply encrypted via a key derived from a pre-shared key (PSK). Here the lack of forward secrecy means that if the PSK is stolen at a later point in time, that data will be decryptable. This is much less of an issue for browsers as these PSK are often short-lived, but it's not always the case in other scenarios.

0-RTT has been pretty controversial, it has generated a lot of discussion on the TLS 1.3 mailing list (see 1, 2, 3) and concerns about its security have taken an entire section in the specification itself.

While I spent quite some time telling you about TLS 1.3's 0-RTT in this post, it is just one example of a security trade-off that WE made, all of us, for the benefit of a few big players. Was it the right thing to do? Maybe, maybe not.

What are the other examples? Well guess why we're using AES-GCM? Because it is hardware accelerated. But who asked Intel for it? Why are we standardizing a shitty WPA 3.0 protocol? Probably because some Wi-Fi Alliance is telling us to use it, but what the F is going on there? Why is full disk encryption (FDE) completely flawed? I am not even talking about the recent Self-encrypting deception: weaknesses in the encryption of solid state drives (SSDs) research, but rather the fact that vendors implementing FDE are never using authentication on ciphertexts! and continue to refuse to tackle the issue via primitives like wide-block ciphers. Probably because it's not fast enough!

Now look at what cryptographic primitives people are pushing for nowadays: AES-GCM, Chacha20-Poly1305, Curve25519, BLAKE2. This is pretty much what you're forced into if you're using any protocol in 2019 (yes even the Noise Protocol Framework). Are these algorithms bad? Of course not. But they are there because large companies wanted them. And they wanted them because they were fast. I touched on that in Maybe you shouldn't skip SHA-3 after Adam Langley's wrote an article on SHA-3 not being fast enough.

We're in a crypto era where the hotness is in the "cycles per byte" (cpp).

All of this is concerning, because once you look at it this way, you see that big players have a huge influence over our standards and the security trade-offs we end up doing for speed are not always worth it.

If you're not a big player, you most likely don't care about these kinds of optimizations. The cryptography you use is not going to be the bottleneck of your application. You do not have to do these trade-offs.

Mathias Hall-Andersen, Alishah Chator, Nick Sullivan and I have released a new construction called nQUIC.

nQUIC = Noise + QUIC

If you don't know what QUIC is, let me briefly explain: it is the last invention of Google, which is being standardized with the IETF. It's a take on the lessons learned developing HTTP/2 about the limitations of TCP. You can see it as a better TCP(2.0) for a better HTTP(/3) with encryption built in by default.

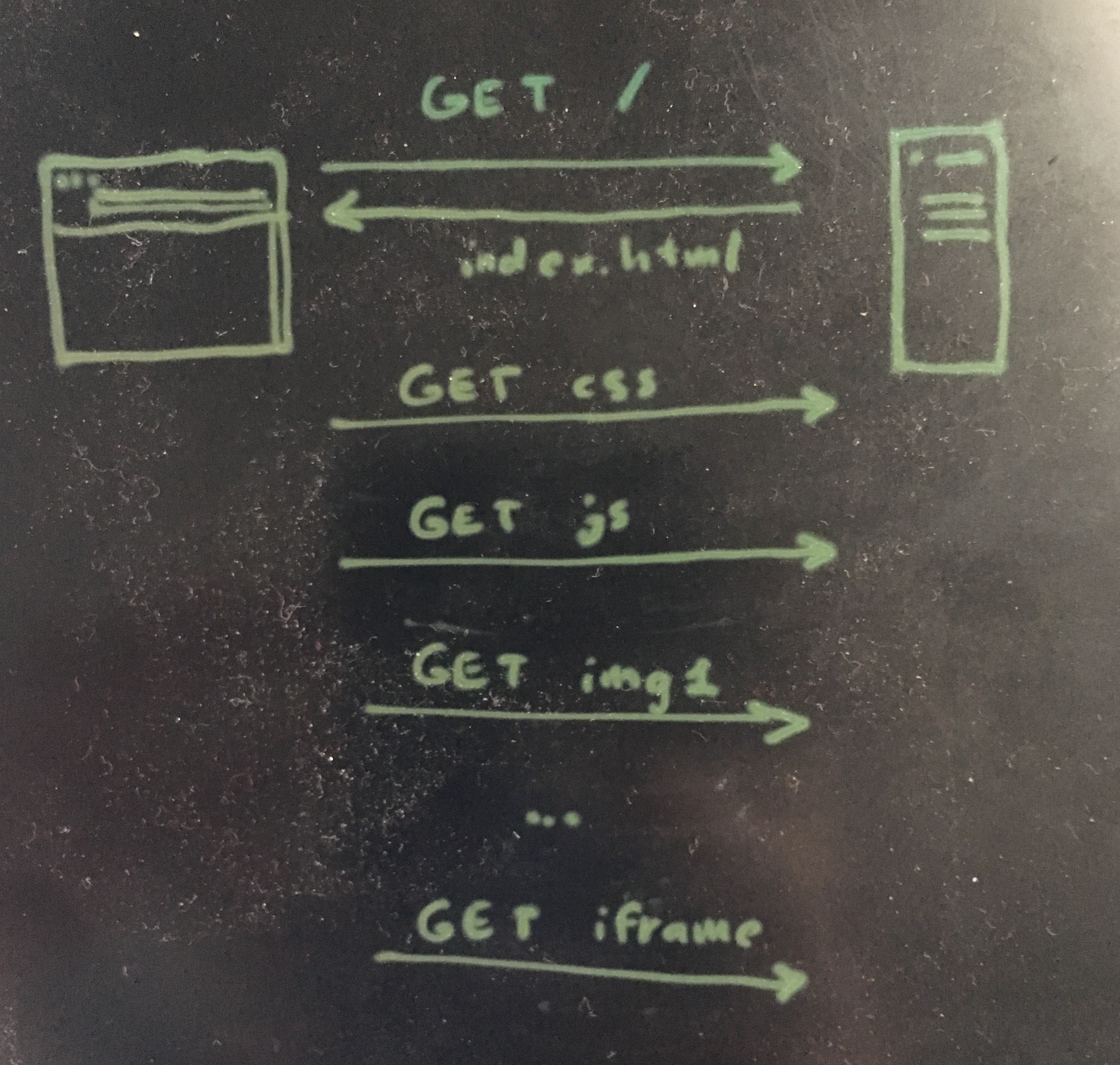

The idea is that, when you visit a page, you end up fetching way more files than you think. There is some .css, some .js, a bunch of .png and maybe even other pages via some iframes. To do this, browsers have historically opened multiple TCP connections (to the same server perhaps) in order to receive the file faster. This is called multiplexing and it's not too hard to do, you just need to use a different TCP port for every connection you create. The problem is that it takes time for each TCP connection to start (there is a TCP handshake as well as a TLS handshake) and then to figure out how fast they can go (TCP flow control).

So in HTTP/2, instead of opening several TCP connections to the same server, we just open one. We then do the multiplexing inside of this one connection.

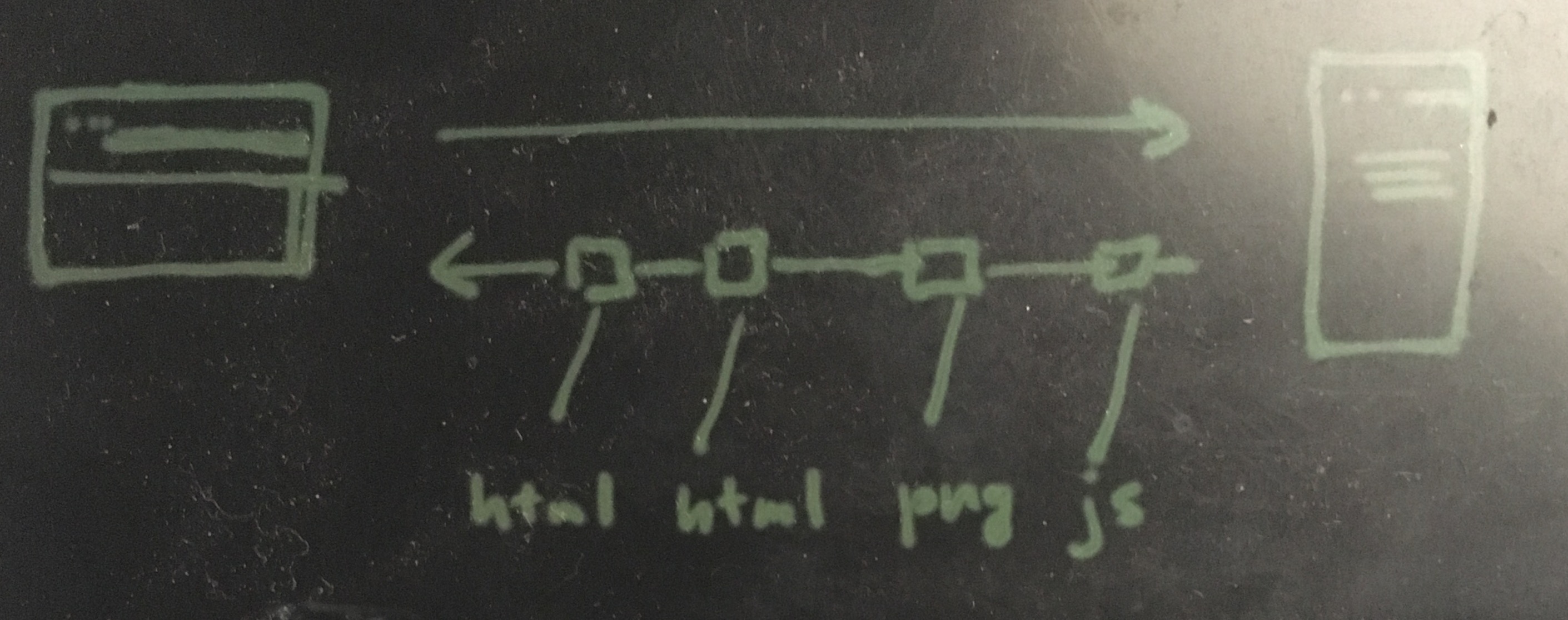

So now you're doing one TCP handshake, then you optimize the connection via TCP's mechanism, and you rely on that to receive whatever the server sends to you. It sends you a bunch of blocks, in whatever order, that you can buffer and glue back together. For example, you might receive some html, then some jpg, then the rest of the html.

One problem is that if faults start appearing on the network, all the different objects you're trying to receive will be impacted, not just one of them. So one ACK can mess every element on the page.

Comes QUIC which fixes these multiplexing issues by re-inventing TCP. Because of middle boxes and firewall issues, QUIC is built on top of UDP instead of creating another protocol on top of IP. It doesn't matter much in theory because UDP is just IP with ports (and ports are useful).

QUIC has different streams, which can carry different content (in order) and are not impacted by issues happening in other streams. You can thus carry the html page in one stream, an image in another stream, the css file in another stream, etc.

On top of that, the people at Google thought that encryption would be very useful to have baked into the protocol instead of making it optional and a responsability of applications (that's what TLS is). Google started this encryption mechanism with QUIC Crypto, which was a very simple protocol, and then decided to replace it with TLS 1.3. While this might make sense for the web, it doesn't really make sense in other settings where simpler security protocols could be used. This is what I talked about in more length in this blog post. Go read it before reading the rest of this post, I'll wait.

You read it? Nice. Well you'll be delighted to see that the nQUIC I've talked about in the first line of this article is exactly what I've been talking about: QUIC secured by the Noise Protocol Framework instead of TLS 1.3.

You can read about the research here. What we found is that it is extremly easy to integrate Noise into QUIC, because it was made to be encapsulated into a lower protocol, whereas integrating TLS 1.3 into QUIC is very hackish. It is also faster, because of the lack of signatures. It is way more secure, thanks to the lack of complexity and x509 parsing as well as the symbolic proofs provided by the research community (see for example NoiseExplorer, and its wonderful talk at Real World Crypto 2019). Finally, we have also added post-compromise security to the protocol, which is a must for long-lived sessions.

After spending many years working in information security, as a consultant, I've had the chance to audit a multitude of different systems invented and developed by many different people. While there is a lot to say about that, the focus of this article is about some of the toxicity I've noticed in the field.

If you're like me, you must have heard the security jokes about developers during conferences, read the github issues of independent researchers yelling at volunteering contributors, or maybe witnessed developer shaming in whitepapers you read. Although it is (I believe) a minority, it is a pretty vocal one that has given a bad rap to security in general. Don't believe me? Go and ask someone working at a company with an internal security team, or read what Linus has to say about it. Of course different people at different companies will have different kind of experiences, so don't take this post as a generalization.

It is true that developers often don't give a damn about security. But this is not a good reason to dismiss them. If you work in the field, it is important to ask yourself "why?" first. And if you're a good person, what should follow next is "how can I help?".

Why? It might not be totally clear to people who have done little to no (non-security focused) development, but the mindset of someone who is writing an application is to build something cool. Imagine that you're trying to ship some neat app, and you realize that you haven't written the login page yet. It now dawns on you that you will have to figure out some rate-limiting password attempt mechanism, how to store the passwords, a way for people to recover their passwords, perhaps even two-factor authentication... But you don't want to do all of that, do you? You just want to write the cool app. You want to ship... Now imagine that after a few days you get everything done, and now some guy that you barely know is yelling at you because there is an exploitable XSS in your application. You almost hear yourself saying out loud "an XX-what?" and here goes your week end, perhaps even your week you start thinking. You will have to figure out what is going on, respond to the person who brought the bug, attempt to fix it. All of that while trying to minimize the impact on your personal reputation. And that's if it's only a single bug.

I have experienced this story of myself. Years ago, I was trying my hands with a popular PHP web framework of the time, when one of the config file asked from me to manually modify it in order to bootstrap the application. Naturally, I obliged, until I reached a line reading

// you must fill this value with a 32-random-characters key

$config['encryption_key'] = "";

Being pretty naive at the time, I simply wrote a bunch of words until I managed to get to the required number of letters (32). It must have looked like something like this:

// you must fill this value with a 32-random-characters key

$config['encryption_key'] = "IdontKnowWhatImDoing0932849jfewo";

Was I wrong? Or was it the framework's fault for asking me to do this in the first place? You got the idea: perhaps we should stop blaming developers.

How can you help? Empathize. You will often realize that security people who have worked non-security development jobs at some point in their career will often understand the developers better AND will manage to get them to fix things. I know, finding bugs is cool, and we're here to hack and break things. But some of these things have people behind them, the codebase is sometimes their own labor of love, their baby. Take the time to teach them about was is wrong, if they don't understand they won't be able to fix the issues effectively. Use language to vehiculate your ideas, sure it is a critical finding but do you need to write that on a github issue to shame someone? Perhaps the word "important" is better? Put yourself in their shoes and help them understand that you're not just coming here to break things, but you're helping them to make their app a better one! How awesome is that?

Sure they need to fix things and take security seriously. But how you get to there is as important.

I also need to mention that building better APIs for developers is an active area of research. You can't educate everyone, but you can contribute: write good tutorials (copy/pastable examples first), good documentation, and safe-by-default frameworks.

Thank-you for reading this.

Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to be an awesome security peep now :)

EDIT: Mason pointed me to this article which I think has some really good points as well:

Another element of a critique-focused report involves the discussion of positive findings of the assessment. As the saying goes, a spoonful of sugar makes the medicine go down.

And indeed, If I liked what I've seen during an audit, I always start a discussion by telling the developers how much I liked the code/protocol/documentation. They are always really happy to hear it and my followed-up critiques are heard way more seriously. Interestingly enough, I've always felt like this is how a good performance-review should go as well.

In my free time in the last years, I have helped (for free) some VCs and friends to figure out what are good opportunities in the cryptography field. I'm at an excellent position to see what is serious cryptography, and even what a promising start up looks like. This is because my day-to-day job is to audit them.

It turns out that it is often quite easy to quickly spot the bad grapes by noticing common red flags. Here's a list of key words that you should probably stay away from: patented, proprietary protocol, one-time pad, AES-256, unbreakable, post-quantum, ICO, supply-chain, AI, machine learning, prime numbers, re-inventing TLS, etc.

In general, if a company focuses its pitch on the actual crypto they use instead of the problems they solve, you might want to turn around. If something doesn't seem right, find an expert to help you. Even Ycombinator got fooled.

Happy New Year.

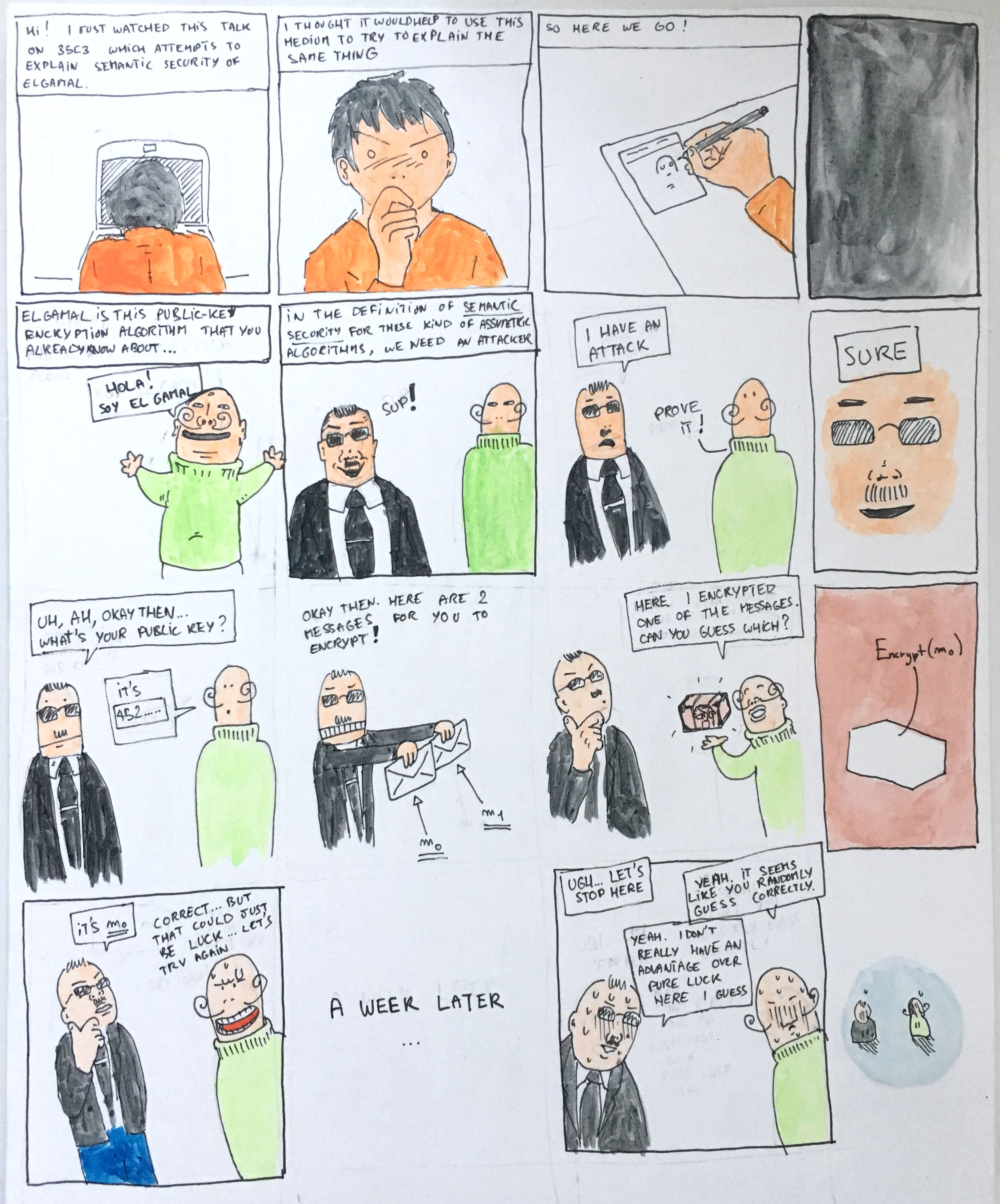

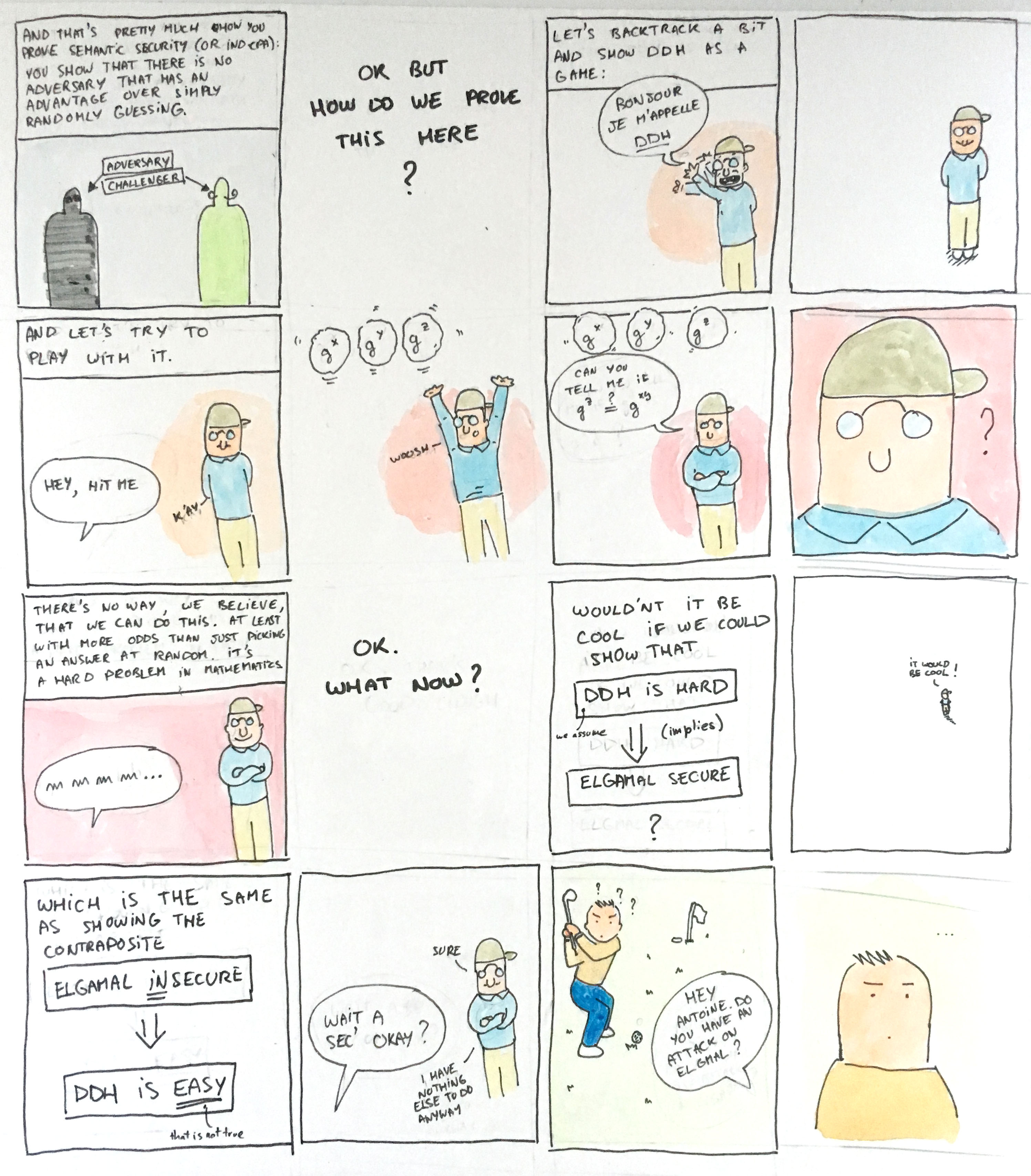

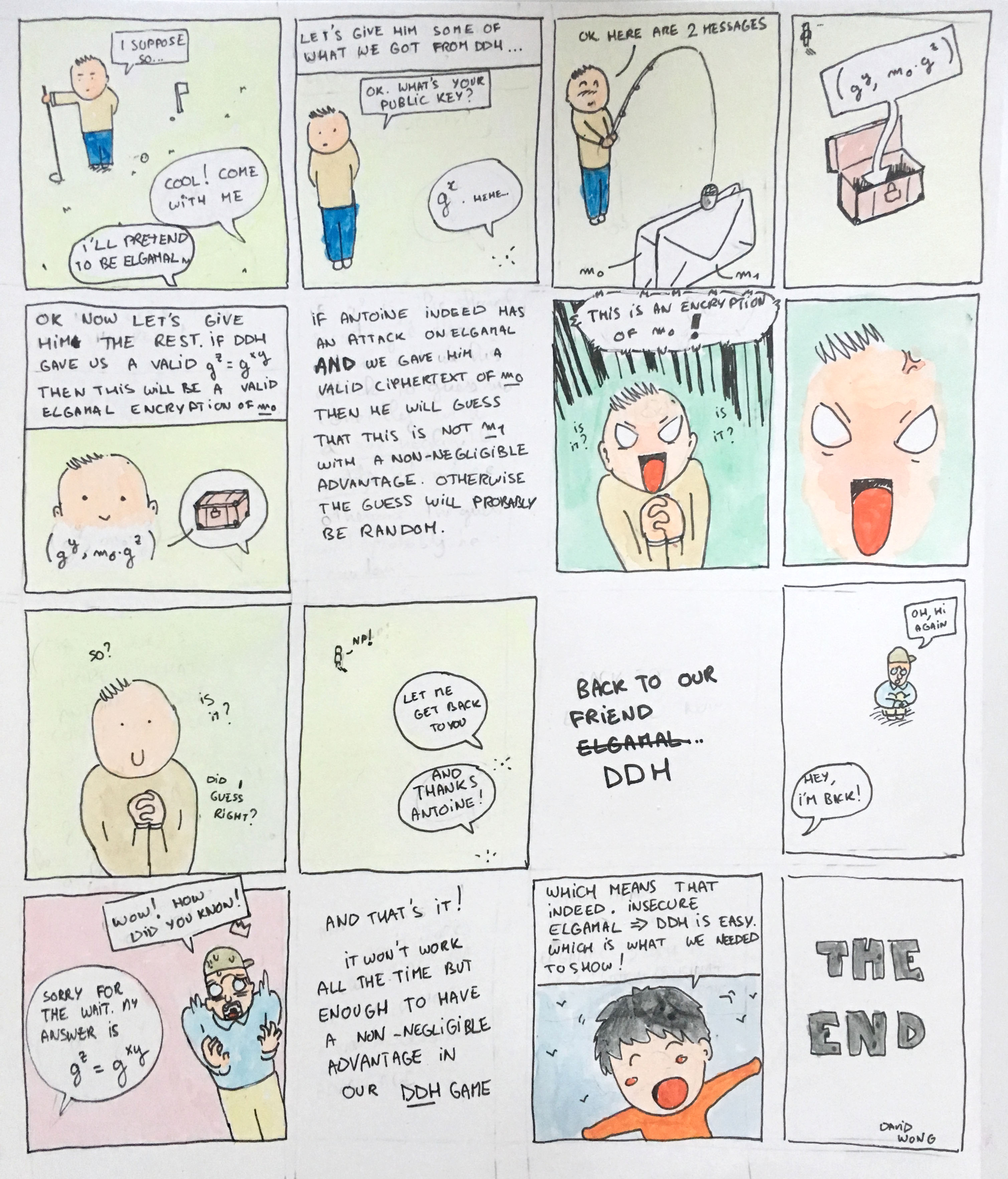

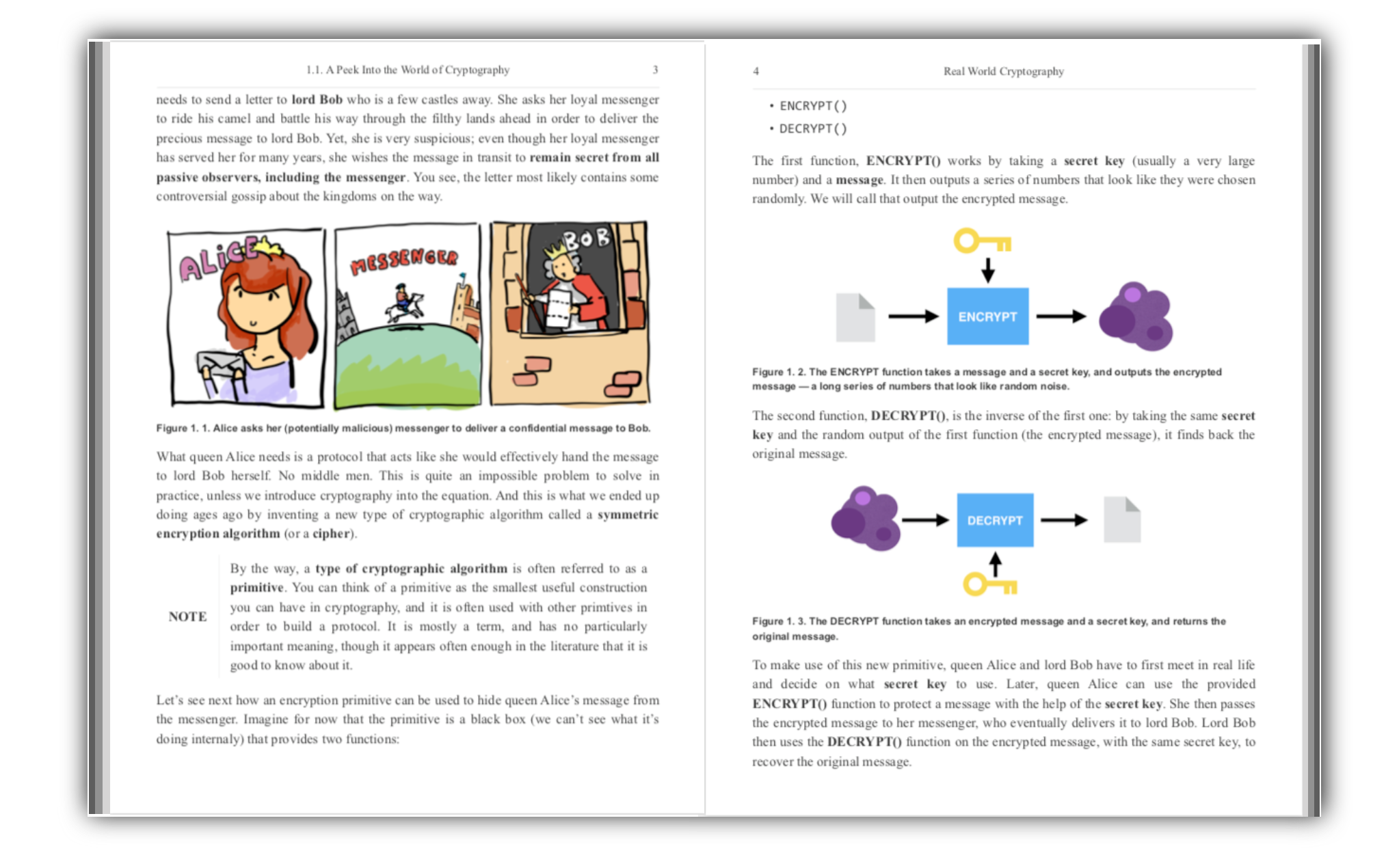

I like drawing, and I haven't drawn in a long time. I figured I could use crypto as an excuse to draw something and start this year in a more creative way :)

(by the way, here is the talk I'm talking about)

Here I glance over a lot of the concepts. I don't explain what is Elgamal or how it works, I don't explain proofs based on games and what semantic security is (and why it is considered insufficient), I don't even explain what I mean by an adversary's advantage. I'm expecting that you will read that on your own and then head here to understand how you can use all of that to prove Elgamal's semantic security.